- Home

- Anna Porter

Hidden Agenda Page 9

Hidden Agenda Read online

Page 9

Today, however, Marsha had so little to add that when Markham remarked that she was showing no real interest in the titles discussed Marsha silently agreed.

Fred Mancuso from Publicity had also worked with Max once, and he and Lynda were in a huddle near the door. They weren’t talking, merely sharing their grief.

Marsha fumbled through the Reprints and category books: Westerns, Mysteries and Science Fiction. They would all be regular releases, the plans had to be confirmed, but they had been set before. The new Romance series was probably doomed to failure; Marsha had only agreed to introduce it after pressure from Larry Shapiro. She didn’t believe new angles could be applied, they’d all been tried—the Simple, the Nurse, the Gothic, the Steamy, even the Divorced Specials. The only gap left was Romance for the Elderly—for that they’d wait until the boom generation hit its sixties.

Lynda revived for the Originals—these were all new titles, not previously published by hardcover houses. Though she wasn’t a wiz at promotion, Lynda did know the manuscripts and was determined to make everyone listen. Originals needed exceptional care so they wouldn’t get lost on the mass-market racks. The promotion people had come well prepared. There would be generic advertising, radio campaigns in Chicago, Minneapolis and Washington. If that worked, they would expand. They had snatched $25,000 from the July genre titles budget to push a second book by a new horror story writer. Markham had made a reasonable argument that he was in the class of Stephen King, and though Marsha was sure he hadn’t read the manuscript, he was, accidentally, right.

The meeting broke up at 3:00 p.m.

Soon after Marsha reached her office Margaret Stanley buzzed with a call from Judith from Toronto.

“Almost sober,” Judith told Marsha, “and wondering about a manuscript Fitz & Harris lost. Or temporarily lost. Something George had and Francis can’t now find.” Would Marsha know someone at Axel, other than Max?

When Marsha said she knew Gordon Fields, the executive editor, Judith asked if she knew him well enough to ask about a manuscript they had acquired from George Harris.

“Why?” Marsha inquired.

Judith told her the whole unlikely story as David Parr had related it to her. Including the price tag.

“Perhaps they would even give you a copy?”

“Can’t think why they would.”

“You could pretend you’re about to make a gigantic bid for the paperback rights.”

“Sure. Without reading it.”

“But Marsha, this might be the missing link. Couldn’t you improvise?”

Marsha grumbled, but agreed to try.

She packed her canvas bag full of manuscripts she had put aside to read on the weekend. Axel Books was two blocks away, on the other side of Fifth Avenue, and visiting in person seemed less insensitive than phoning Gordon Fields.

***

Marsha hadn’t been at Axel’s offices in months. Usually Gordon suggested lunch when he had an important book to discuss, or he sent over manuscripts with short, witty notes telling her why they were ideal for the M & A list.

The double elevator doors opened on a pair of policemen, one with a clipboard in his hand, the other leaning over the receptionist, and using the main switchboard phone. The one with the clipboard looked up at Marsha.

“You work here?” he asked, jerking his head in the direction of the glass doors leading to the editorial department. Marsha wondered why so many New York policemen looked as if they had slept in their uniforms. This one was crumpled all over, had a day’s growth of beard and dark perspiration stains under his arms and down the middle of his chest.

“No.”

“What’s the purpose of your visit?” He sounded like an immigration official.

“Business,” Marsha said, just as automatically.

When the policeman saw she wasn’t going to elaborate, his lip curled slightly in disgust.

“What kind of business?”

Valiantly, Marsha defeated the desire to say “soliciting.” Cops don’t like being straightmen.

“I’m going to see Gordon Fields.”

“We’re not allowing visitors today.”

“I don’t see why not,” Marsha said with her best rendering of a cool Bette Davis pose. “Mr. Grafstein was a very nice man, but we all have to go on.” She tried a little smile. Not much—she didn’t want him to think she took Max’s death lightly; but about the right amount to suggest that, uniform or not, we are all only human.

The policeman checked his clipboard.

“Gordon Fields,” he repeated. He did not return Marsha’s smile. “Executive editor,” he added.

“Yes,” Marsha said. The fellow was obviously impressed with titles and she wanted to drive home her advantage. “Mr. Fields would be very disappointed if he discovered I was here and had not been allowed to see him. Perhaps, if I can’t go in, you could let him come out.”

He lowered the clipboard and looked at his partner. Marsha could sense him weakening.

“I’m sure Mr. Fields would really appreciate that,” she said as softly as she could, edging toward the reception area.

The policeman sauntered over ahead of her.

“Miss,” he called to the receptionist, “could you buzz Gordon Fields and tell him there is someone here to see him…”

The receptionist gave Marsha her quizzical look.

“Marsha Hillier,” Marsha said decisively.

“You been here before?” the policeman asked while the receptionist dialed Gordon’s extension.

“Yes. You’re investigating the murder?” she asked, hoping to occupy his attention while Gordon registered his astonishment at her sudden appearance.

“I’m not with homicide.” The policeman shrugged. “Looks like a standard mugging, though…you’re not a reporter, are you?”

“No. I work with books,” Marsha reassured him. “If you’re not with homicide, why are you here?”

“Burglary,” he said.

“When?”

“Last night.” The policeman pointed at the set of red plastic-covered chairs and couch in the reception area. “You can wait for him there.” He turned on his heel and went back to the elevators.

Gordon came flying through the door just as Marsha was about to sit.

“Marsha darling, how good of you to come by!” he shouted in his disarming falsetto voice. His arm went around Marsha’s waist and he folded the two of them into the couch. “These are terrible terrible times. So tragic. Max with a whole life still ahead of him.” Gordon shook his head. A thin tuft of sandy hair trembled on his forehead. “We’re all in shock, you know. Every one of us.”

Marsha patted his knee encouragingly.

“So horrible. Ugly. You should have seen it this morning. How someone could do that…”

“You mean the burglary?” Marsha asked.

“My dear, it’s not a simple burglary,” Gordon’s voice rose again. “It’s vandalism—of the most brutal kind. Everything’s been turned upside down. Wrecked. Desecrated. Manuscripts strewn about like confetti. It’s impossible.” He gestured weakly with his hand. “We’ll never be able to sort it out. Never!”

“Did they take anything?” Marsha asked.

“Who knows? How will we ever tell? In that dreadful mess…and the smell. My dear, the smell! This morning—you know I’m here at 7:00—the smell was the first thing that hit me. How someone could do that?” He shook his head again. “And why? Why?”

“What you do mean ‘the smell’?”

“Someone had…they relieved themselves all over the papers. And the walls. Everywhere. The police even took a sample.” His eyes brightened for a moment. “In a glass vial, would you believe.”

“And I thought they only kept fingerprints,” Marsha said.

Gordon chuckled a little, then composed his features into the original expression of agitated grief.

“Why don’t you all go home?” Marsha asked.

“The police. They’re question

ing everybody about where they were last night. As if we were all suspects. Personally, I don’t believe anyone who works here would do a thing like that. They might have tried to burn the place, that’s possible. Heaven knows I’ve thought about burning it myself from time to time. But not piss all over it. Not literally, anyway.” He allowed himself another tiny hrumph of amusement.

“Poor Max. It’s a good thing he didn’t have to suffer through this degradation. His office was the worst, you know.” Gordon clasped his hands over his chest, sighed and lowered his eyelids over his pale blue eyes. “All his drawers dumped on the floor. His confidential files. His little bar turned upside down. All that broken glass.” He hissed the last words through pursed lips. “They broke open the safe. His collection of old books and original manuscripts was ransacked. We can’t tell whether we’re dealing with a thief or a maniac. May have been some guy whose work we turned down. Lots of those around. A nut with a few of his buddies. Chances are,” he jerked his thumb toward the two policemen, “we’ll never know. Anyway, my dear, what brings you here? Sympathy?”

Marsha told him she was hoping to find a manuscript sent to Max from Fitzgibbon & Harris, Toronto. She admitted she knew very little about it, except that Max had mentioned a big sum of money. Over $100,000.

“What’s it to you?” Gordon asked, suddenly businesslike.

“We’re looking for a major paperback deal in Canada,” Marsha improvised. “For September, and we haven’t much time left. I thought it would be quicker to pick up a copy here.” Then she had to admit she couldn’t remember either the author’s name or the title. But how many lead titles would Max pick up in a year from Canada? Shouldn’t be hard to find.

Gordon said he’d ask around but couldn’t promise much. Not the way it was now. Marsha should at least get the details.

“Max was,” Gordon said, looking mournfully back through the glass partition, “rather secretive about his own special projects. He liked to surprise.”

They exchanged some Max stories—affectionate, but entertaining—and Gordon said he’d call if he found what she was seeking.

Twelve

THE CHILDREN TOOK it well until Judith told them they were going to spend the weekend at their grandmother’s. At sixteen, Anne thought she was perfectly capable of taking care both of herself and of her brother, and Jimmy didn’t want to be taken care of by anybody. Least of all Granny, who was never satisfied with anything he did.

“She has the tact of a hippo,” Anne agreed, and made it quite clear she wouldn’t sing after dinner. Her grandmother was bound to sit at the piano and expect to accompany Anne in a golden oldie she’d taught her.

Judith offered to make their favorite meal of spaghetti and meatballs, but they felt too surly to be cheered by that. Next Judith tried for sympathy. The trip was a birthday present, and how could she have a good time in New York if she worried about them. They had to understand how much it meant to her to know they were safe, even if it wasn’t much fun at Granny’s.

“You’re still going to have tonight on your own,” Judith said to their united backs as they lined up on the couch in front of the TV set. They were riveted to a Big Mac commercial, absorbing every juicy word. Rigid. Unforgiving. That’s what you get for running a democratic household, Judith thought. Charming.

She packed elaborately, for all weather conditions and occasions, grabbed her notes, her copy of the unfinished Harris and Nuclear Madness articles, a couple of paperbacks for the road and an umbrella to ensure it wasn’t going to rain.

There was little point in trying to force them to accept her position, so she just ruffled the back of Jimmy’s hair, rough and springy like his father’s, kissed them both lightly on the forehead, deposited two twenty-dollar bills on the coffee table and left.

All the way to the Allen Expressway she was swearing under her breath at their lack of understanding, and at why anyone sensible would have kids. Going past Yorkdale, she remembered bringing them here shopping for specials in kids’ clothes and toys, and how they had ice cream cones and chips, and how she always forgot where they had left the car. And she remembered the first night after James left, when she was discovering how large and foreign the house had grown around her, Anne coming down the stairs in her white flannel nightgown and wrapping her arms around her mother’s waist, saying, “Don’t worry, Mum, I’ll take care of you. I truly will, you’ll see.”

By the Airport Road exit, she was already beginning to miss them.

***

She had asked for an aisle seat in the nonsmoking section, figuring she should manage without cigarettes during the short flight to New York; she had forged her way through half a pack already today. She tried putting the finishing touches to her Nuclear Madness story, but as soon as the no-smoking lights went off she was lining up at the back for a smoke. She chatted with a friendly stewardess about the difficulties of quitting bad habits and ordered herself a spicy Bloody Mary mix.

When she returned, there was a small yellow envelope on her seat cushion. She stared at it for a moment, then bent over for a closer look. It had her name on it, neatly scripted in green felt pen. She picked it up between thumb and forefinger and turned it over: an ordinary yellow envelope.

The stewardess, attempting to squeeze by with a sandwich tray, implored her to sit down.

She opened the envelope along the glue line and found a piece of yellow notepaper, serrated along one edge where it had been torn out of a book. There were four even lines in the same neat, green felt pen, centered on the page:

I know who you are and what you want.

You need help from here on. I can help you.

Meet me at F.A.O. Schwarz second floor

3:00 p.m. Saturday. Near the trains.

Judith turned the paper over in her hand. The other side was blank. She rose and swiveled toward the back of the plane. People were reading, eating, drinking, airplane style. The man in the seat immediately behind hers tried a half-hearted smile, then returned to his Globe and Mail. She went up the aisle, wheeled around at the toilets and walked back the length of the plane, peering at each passenger as she passed. No one was familiar and no one showed much interest.

Cautiously she examined the woman next to her. She was so engrossed in her book, hunched forward, her face close to the page that she wouldn’t have noticed anything short of an electric storm. It was worth a try, though.

“Excuse me,” Judith said, then again louder: “Pardon me.”

The woman looked at her blankly.

“Did you happen to see who put this,” indicating the envelope, “on my seat?”

“No,” the woman replied, and buried her face in the book again. Anyone who had fought her way through more than one thousand pages of War and Remembrance deserved to be left alone.

She asked the navy-blue, sailing-away blazer across the aisle, but he hadn’t noticed anyone either. Of course both of them could have been lying, but why?

She re-read the note. One place she rarely missed on her visits to New York was F.A.O. Schwarz. No question she’d be there at 3:00 p.m. tomorrow.

After they landed at La Guardia, she looked around again. No one paid any attention to her.

She dragged her suitcase down to the taxi stand. Ridiculous. Here she was carrying three suits, four dresses, two pairs of slacks, a coat. Even if she decided to change three times a day, she had brought too many clothes. Her wardrobe had grown as a direct result of the argument with the kids. Arguments made her feel insecure and insecurity made her feel uncomfortable. Multiple choice would at least afford her the chance to feel uncomfortable in a full range of outfits.

She heaved the bag into the front seat next to the driver—why don’t New York cabbies help with your luggage?—and turned for a glance at the people in the line-up. Second from last, there was a man who looked vaguely familiar. He was about forty, wearing a rumpled raincoat under a rumpled face, a face that had started out with too much skin. Creased, but friendly. She h

adn’t seen him on the plane. But she had seen him somewhere before. She waved at him, and slid into the cab.

Then she remembered. It was the man from the Roof Lounge of the Park Plaza. He had been sitting at the next table when she had martinis with Max. And he had seemed familiar even then.

Thirteen

FOR JUDITH, MARSHA’S apartment held all the fascination of a Bloomingdale’s window for a Sudbury housewife. It reflected a perfectly cool, composed vision of all her aspirations to glamour. Every piece—and in Marsha’s apartment, there were pieces, not furniture—fitted into its own niche, and yet belonged with all the other pieces, polished, expensive.

Marsha had a fondness both for antiques and for the ultra-modern. The living room had two Louis Quatorze straight-back armchairs and a marble-top table, English from the same period. Judith had coveted the two turn-of-the-century Tiffany lamps ever since Marsha received them as a gift from her turn-of-the-century Russian lover. The curtains were blue and gold China silk, a recent acquisition from a publishers’ conference in Hong Kong. There were Persian rugs on the hardwood floor. Marsha had never liked the wall-to-wall broadloom look, it didn’t allow for variety. Nor would it have allowed for her frequent changes of mind.

The couch was a semicircular creation by Igor. It had been built to fit around three sides of Marsha’s living room and to offer a fair view over the sumptuous trees of Gramercy Park.

The paintings were originals. None of the prints was numbered above fifty. She had Andy Warhol in the bedroom, Andrew Wyeth in the study, a signed Ansel Adams in the bathroom, and a Hopper house-in-landscape in the living room.

She had started out with a few good pieces twenty years ago when she moved to New York, and added to them each year. The Hopper, though, had come from daddy Hillier, as had the beginnings of the glass-elephant collection that Marsha kept in the eighteenth-century bow-legged glass cabinet in the dining room.

Deceptions

Deceptions Hidden Agenda

Hidden Agenda The Appraisal

The Appraisal Mortal Sins

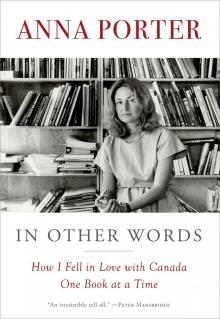

Mortal Sins In Other Words

In Other Words