- Home

- Anna Porter

Mortal Sins

Mortal Sins Read online

MORTAL

SINS

Anna Porter

FELONY & MAYHEM PRESS • NEW YORK

For Puci and Julian

My thanks to Maria des Tombe for research, Jean Marmoreo and Michael Weinstock for medical facts, Jim Young, who is a real coroner, Bob Wilkie and Malcolm Lester for encouragement and corrections, John Pearce for his forbearance, and Lorant Wanke for remembering how to get to Eger.

CONTENTS

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

Twenty-One

Twenty-Two

Twenty-Three

Twenty-Four

Twenty-Five

Twenty-Six

Twenty-Seven

Twenty-Eight

Twenty-Nine

Thirty

Thirty-One

Thirty-Two

Thirty-Three

Thirty-Four

Thirty-Five

Thirty-Six

Thirty-Seven

Thirty-Eight

Thirty-Nine

One

SHE LIFTED THE HEAVY tear-shaped brass knocker and let it fall. The sound was like a sharp high-pitched drumbeat that echoed back and forth between the two gray marble pillars of the porch. The pillars served to dwarf the unwary visitor, in case the broad granite steps, the armed guard at the gate, and the towering poplars lining the long, winding driveway had failed to cut her down to size already. The driveway, according to Business Week, was paved with a fine gravel of meteorite. The marble was from Carrara, where Michelangelo had chosen his. “Awesome” was the word that came to Judith’s mind. One of Jimmy’s favorite words had finally found a fitting occasion.

The meticulously carved oak door opened about ten inches, wide enough to afford the thin white-haired man inside a thorough inspection of the visitor. Only his eyes moved. The rest of his body, elegantly draped in three-piece black suit and matching bow tie, was poplar-straight.

“Yes?” he asked, barely moving his lips.

“Hello,” Judith said brightly. “I’m Judith Hayes. I’m here to see Mr. Zimmerman.”

“Yes,” he repeated, “you are expected.” He opened the door wider and made room for Judith to enter.

“May I?” He was already behind her, expertly lifting the burgundy coat, her best, by the shoulders and slipping it over one stiffly held arm. God forbid he should notice the lining’s frayed down the back.

“Please follow me,” he suggested with a slight nod toward the marble-tiled reception area. The pink marble ran partway up the wall, formed a small ridge, and stopped where the white and pink flocked wallpaper began. There were several large horse prints in gold-painted frames, a small nude female statue on a pedestal—probably Greek—a Byzantine crystal chandelier, and a marble-top table with a huge silver dish that served as an ashtray. To the right, a white-carpeted staircase with oak banisters.

The butler turned left, swept past a pair of closed doors with shiny brass handles, and pointed the way through a third.

“Mr. Zimmerman will be with you in a moment.” He bowed slightly and signaled her to enter, then turned ceremonially and left.

He’s been watching too much Upstairs, Downstairs, Judith thought.

The waiting room offered few comforts. A library of brown leather and gold ran from floor to ceiling. In the center stood a huge oblong table of dark mahogany with heavy carved legs and a straight-backed chair placed dead in the middle of each side. Gold candelabra. In one corner a Queen Anne writing desk with its round-shouldered chair, gold letter opener, and Victorian inkwell and pen.

She remembered her mother had once bought a yard and a half of leather-bound books to fill an empty space in the living room. “You’re not supposed to read them,” she scoffed at Judith’s father. “They’re the decoration. Nobody reads leather-bound books...”

Curious, she approached the shelves only to confront an army of Encyclopaedia Britannica and Winston Churchill.

Near the gray stone fireplace, she found two maroon wing chairs facing each other, turned slightly toward the dead logs and two bronze wolfhounds. She chose the chair farthest from the door. The touch of cold leather made her shiver.

She tried a number of casually relaxed positions, ending up with legs crossed, knees tilted to one side, arms akimbo, and desperately needing a cigarette. Times such as these brought to mind why she had begun to smoke in the first place—exactly 24 years before the day that she’d last quit. It had been her first New Year’s Eve party. She’d worn a red taffeta dress with frills at the neck and wrists, a bow in the back. Marjorie, her mother, had puckered her lips in anticipated disapproval as she warned James to make sure he brought her home by 1 A.M. The Big Concession. The dress had been a hideous miscalculation. She stood out in the crowd—a clumsy, oversize red blob. But she had been most aware of her hands, hanging like useless talons at the ends of what she believed were her simian arms. And then James had offered her a cigarette.

“Mrs. Hayes—I apologize.” A deep baritone voice whisked her back to the present before she’d taken one whiff of the sinful weed.

He stood in the doorway, his head mere inches from the top of the frame, his shoulders almost blocking the light from the hall. He instantly dwarfed the room. Six-foot-four was what Business Week had said: “The man bestrides the earth like a Colossus...”

“Mr. Zimmerman?” Judith asked, quite unnecessarily, as she struggled to her feet.

“I was caught by the phone just as I came to greet you. Blasted things have come to rule our lives.” There was a touch of an accent on “things,” but she may have been waiting for it.

He was striding toward her with jaunty, energetic steps, his jacket flaps swaying with the motion, his right hand already extended. Once he reached Judith, he cupped her hand in his own broad-palmed hands, dry flat fingers that scraped her wrist. His face, as he looked down at her, seemed impossibly far away. She had to crane her neck to meet his eyes. They were a bright, transparent blue, set wide apart, shaded by almost white eyelashes and thick, jutting gray and white eyebrows. A columnist had once conjectured that it took a full ten minutes each day to untangle and shape them.

His hair was white and starting to recede into a widow’s peak. His skin seemed bronzed and leathery, the deep wrinkles around his mouth and eyes like squint lines against the sun. The toll exacted by all that tennis, sailing, golf. Or was it from sitting in the bleachers watching his Chicago baseball team, now training somewhere in Florida?

“Would you like something to drink?” he asked. “Coffee, perhaps? Some wine? Tea?” He pushed a button under the arm of the other maroon wing chair.

“Tea, I think,” Judith said, although she had intended to request a gin and tonic. On reflection, the atmosphere was all wrong for gin.

“Tea for the young lady, Arnold, and coffee for me. Double espresso, please,” he said, not glancing behind him, where the butler had materialized in the doorway.

Judith gave a small internal whinny at the “young lady” and told Zimmerman how pleased she was that he had agreed to the interview. He hadn’t granted one since 1977, and that had been rather a formal exchange conducted at his New York office. No photo opportunity.

“You don’t find this formal?” Zimmerman asked, indicating the room. His pale eyes had fixed on Judith’s face, the white lashes steady, the corners of his mouth pulled into a polite, qui

zzical smile.

“It’s more formidable than formal,” she said, “but it is your home, and I appreciate being here.” She was pulling her notebook out of her purse—setting up the props.

“Don’t you use a tape recorder?” he asked.

“No. I trust my notes.” Judith had hated tape recorders ever since hers had broken down ten minutes into a habitual bank robber’s confession and she hadn’t noticed it wasn’t recording.

“Jensen had a handsome Japanese job which he stuck on the desk in front of me,” Zimmerman went on. “Apparently he hadn’t the foresight to speak into it himself. That made it very difficult later to discern what his questions were. Or what I had said yes to. A clever journalistic trick, I’m told.” He gave her a long, calculating look. “What do you think?”

Judith had read the Jensen story and hadn’t found it particularly clever, except for the bit about the old lifeboat theory, where Zimmerman had agreed that if the whole world were fed and clothed at the expense of the wealthy nations, there would be no standing room left for anybody, and we’d all drown. “Jensen is out of work and that’s not very clever,” she said.

Zimmerman laughed. “I know,” he said, keeping his voice light. “You’re never out of work, are you, Mrs. Hayes?”

“Can’t afford to be,” Judith said.

Arnold served her tea in translucent bone china on a silver tray.

“Perhaps we could start there,” Judith suggested. “Why you’ve agreed to talk to me, when you’ve been avoiding the press for some ten years.”

“Avoiding?” His head tilted to one side, he contemplated the word for a second. “No. I haven’t been avoiding the press. I merely haven’t had time for it or reason to befriend it. In America there is a tacit assumption that men in business, like politicians and movie stars, owe the press, on demand, interesting explanations for their actions. They are expected to be available for astute comment, for photographs, for revelations about their personal lives. What’s astounding to me is that so many businessmen comply. I’ve tended to consider the whole thing an intrusion, and not fair to my family and associates—such as they are. Besides, I derive no joy from seeing my words in print.” When he laughed his whole face wrinkled up, layer by layer, radiating outward. “But all that has changed now. Right?”

“Has it?”

“Clearly,” he said with mock earnestness, “or we wouldn’t be here.”

“Why has it changed?”

“Perhaps I’m tired of being a recluse. Perhaps I’m learning public relations. Or I want to curry favor with the Chicago sports fans. Or I liked what Marsha Hillier had to say about you. Does it matter? Fact is you’re here, so let’s get on with it.” He sat back, crossed his elegantly tailored pant legs, placed his elbows on the arms of the chair, and intertwined his fingers in relaxed anticipation.

Lovely. Next. “Let’s talk about Pacific Airlines,” said Judith. “You told the remaining shareholders that its management team would be ill suited to administer an average Albanian household—”

“No disrespect to your Albanian readers,” Zimmerman interrupted.

“—and that your first move as chairman would be to cut the fat off the corner office gang. That’s pretty tough language coming into the stewardship of a new company. I wondered whether you used it partly in retaliation for the battle they waged to keep you out.”

“Only partly. Mostly, I never cease to be amazed at the lengths executives will go to keep their Lear jets. Their primary responsibility should be to the shareholders’ investment they have been entrusted with, not to their own job security. Now and then the two coincide. Not so at PA. During the past four months, that group of management gurus devoted all their time to hunting for another buyer. A white knight,” he whispered conspiratorially, “and a blind one, too, I bet, who couldn’t read financial statements or work out for himself why Pacific was declaring a loss, the second year running, when American Airlines’ profits are up again, and National is diversifying its asset base. There is nothing wrong with Pacific that a new team can’t correct.”

“You have fired the top executives?”

His eyebrows shot up to affect a look of exaggerated innocence.

“I’ve been hoping they’d all leave in protest. After all, I’ve been questioning their competence in public. It would save us all a lot of bother if they admitted defeat.”

“Will you run the company yourself?”

“Men like me, Mrs. Hayes, run things. We’re good at discerning larger patterns, but not at filling in the details. Joe Willis, the new president, will take care of those.” He emptied his coffee cup with a loud slurp and put it back on the silver tray. “More tea?” he asked Judith.

She shook her head.

Zimmerman summoned Arnold for more coffee for himself.

“Mr. Dale, a member of the Pacific Airlines board since 1983, has hinted that the union was concerned about your—”

“Did you say concerned?” Zimmerman hooted. “Now there’s an understatement. Afraid, panicked, terrified, maybe—but definitely not concerned. It doesn’t take a genius to discover I’m not a man to stand around discussing increased benefits, fewer working hours, and ironclad job security while the company goes down the tube. The unions have run Pacific Airlines for 15 years. They even have two representatives on the board. They’ve bought themselves a namby-pamby management which has let them have it their way all those years. Well, they’ve had their chance. Now it’s my turn.” He was leaning forward in the chair, his shoulders squared, every bit the fighter—or at least playing the part with conviction.

“You have some 14,000 people with union contracts at Pacific. You can’t run the airline without them—”

“I can’t? Hmm...” Once more that quizzical smile. “I doubt if you have examined all my options. Similarly, I doubt if they have. When they do, they’ll realize that I aim to put PA back on its feet, with or without their help. It’s their choice which.” He watched Judith writing for a second, then he asked, “In their place, what would you do?”

“I don’t know all the facts,” she said. “But I guess I wouldn’t give in too easily.”

“Would you put your job on the line? On a point of principle?”

Another trick question? “Yes, I think I would.”

Zimmerman nodded. “You have the luxury of immutable principles. Most people don’t.”

Before she had a chance to respond, the door flew open to admit a small, balding man with gold-rimmed glasses, fur-collared coat, and blue silk scarf. He carried two immense attaché cases that looked as if they weighed more than a man his size would want to lift. To Judith’s surprise, he tossed the cases onto the mahogany table and continued his progress toward the fireplace.

Zimmerman completely ignored his presence.

“God, Paul,” the man shouted, pausing to catch his breath, “I’ve been trying to get you for two hours. The damn phones are out or something. Both your lines busy, busy, busy. Drove me crazy. In the end, I figured I’d need you to sign things, so I braved the damn blizzard and I came myself—” Blizzard? A few desultory flecks of snow wafted against the windows.

He had either just noticed Judith, or only now decided to acknowledge her. His squeaky voice rose another note. “But you’re not alone...” He spread his short legs, rocked back on his heels, and stuck both hands into his pockets. “Well...”

Zimmerman inclined his head to one side. “Judith Hayes, meet the illustrious Philip Masters, my current mouthpiece and occasional counsel. Mrs. Hayes and I were in the midst of reviewing my interest in Pacific.”

“You were?” Philip Masters squawked, staring at Judith.

Zimmerman chuckled at Masters’s consternation. “In a manner of speaking. Mrs. Hayes is working on an abridged version of my life story. It’s what they call, in her trade, a personality profile.”

“And Pacific Airlines?” Masters spluttered.

“We had to start somewhere,” Zimmerman said.

“But Paul—” Masters rocked even farther back on his heels, till Judith thought he was in danger of landing on his ass.

Zimmerman cut him off in mid-sentence. “I invited Mrs. Hayes,” he said. “She is a friend of Marsha Hillier, Colonel Hillier’s daughter.”

“Oh,” Masters said. “And who do you work for, my dear?”

“I freelance. But this story is for Finance International,” Judith said. She hadn’t even flinched at “my dear.”

“Sort of like you, Philip, a hired gun,” Zimmerman said. “She’ll work for whoever makes her the best offer.” His voice was gentle despite the slam it aimed at both of them. Judith was surprised that Masters didn’t protest. Perhaps he was used to this sort of banter. He merely turned his back and started for the table and his two briefcases. “Right, Philip?” Zimmerman didn’t let go.

“I don’t take any job that comes along, only the ones I choose,” Judith said to fill the void.

“More luxuries,” Zimmerman murmured. “How very convenient.”

Masters spoke at last. “As I mentioned,” he said with a tight grin, “I have a few things for you to sign. Closings today. Shouldn’t take more than ten minutes. Maybe Mrs. Jones—”

“Hayes,” she muttered.

“—will excuse us?”

Zimmerman stood up slowly. From the careful way he lifted himself, palms steady on the arms of the chair, Judith guessed he had arthritis or rheumatism—the only hint so far of his age.

According to Who’s Who, Paul Zimmerman was 58 last July. Born in Hungary. Educated in Montreal. No degrees listed. Sixteen chairmanships, including Loyal Trust, Monarch Enterprises, Domcor, Royal Bus Lines, New York Securities, Southern Airlines (Pacific Airlines hadn’t made it into the current edition), Wheatsheaf Resources, and a bunch of oil and gas companies that Research had indicated were each in the $12-million to $25-million net worth range. Monarch itself had seven separate subsidiaries, each wholly owned, each with its own CEO reporting to the holding company.

Deceptions

Deceptions Hidden Agenda

Hidden Agenda The Appraisal

The Appraisal Mortal Sins

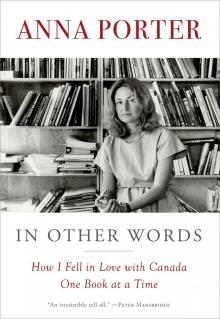

Mortal Sins In Other Words

In Other Words