- Home

- Anna Porter

Hidden Agenda Page 10

Hidden Agenda Read online

Page 10

There were, Judith concluded once again, some advantages to having started with money. The relative squalor of her own quarters could not be attributed solely to the bad habits of a misspent youth and the price she had paid for them, in children and other indiscretions.

When Marsha let Judith into the apartment the comforting glow of the Tiffany lamps was complemented by the smell of Wiener schnitzel frying in lemon butter.

She took Judith’s suitcase.

“Jeez, you’re staying for a year?” she exclaimed and led her, one arm around her waist, to the couch. “Kick off your shoes. You must be exhausted after carrying that thing around.” She shoved Judith’s bag into the study. “Martini?” she asked.

“Great,” Judith said as she eased into the soft cushions. She lit a Rothmans, she was entitled to it, put her head back and closed her eyes. “Glad to be here.”

It was like old times. Returning from summer holidays, best friends at school; the stored memories bubbled to the surface. She gazed at Marsha’s smiling face as she lifted her glass. Still the full lips, the long tapered nose, deep blue eyes, the light curved eyebrows, high forehead framed by soft wisps of blonde hair which curled around her face and clung to the back of her neck where the hair had been pulled up into a loosely-formed chignon. There were a few white strands, more like highlights, and some faint surface lines had crept in under her eyes and around her mouth but, in this light, she hadn’t changed much since they boarded at Bishop Strachan. Then Marsha had looked older than her years. Now she had grown into her body.

“Was it hard getting away?” Marsha asked.

“Like pulling teeth. The kids loathe spending the weekend with my mother. I can’t altogether blame them.”

“Aren’t they old enough to be left to their own devices?”

“Probably. But I don’t feel comfortable when they’re alone. I worry.”

“Don’t you worry when you leave them with your mother?”

“No. I came through all right, didn’t I?” Judith said with a shrug.

“Did you?”

Marsha laughed her deep resonant laugh and changed the subject. “How was your trip?”

“Strange,” Judith said as she dug in her purse for the small yellow envelope. “I got a message on the plane.” She handed it over.

Marsha read the four green lines carefully.

“From whom?” she asked.

“I don’t know.” She told Marsha about her search.

“You think you looked like an ass wandering about the plane, you should have seen me trying to explain to poor Gordon Fields what I was doing at Axel the day after Max died, with the whole house turned upside down—they’d had a burglary—and me trying to locate a manuscript I couldn’t describe.”

Judith told her Alice’s theory. Not impossible Max would have been looking for an acquisition. Axel had the energy and the resources. And Francis wouldn’t want the prospect marred by scandal.

Marsha brought out a brass tray with two plates of herring in sour cream served on lettuce and two small glasses of Bols gin to drink with the herring, Dutch style.

“I hope you still like this,” she said.

“You remembered,” Judith said, surprised.

“It’s not hard to remember. You’re the only person I know who likes the slimy things. Besides, two years ago we went hunting for them together at a succession of restaurants that serve food after midnight. You had a terrible longing for them. I was afraid you were pregnant.”

As they started dinner, Judith told Marsha all about David Parr’s visit. Marsha recognized the look on Judith’s face.

“You don’t mean to tell me that you’re actually falling in love with a policeman?” The way Marsha said “policeman” made the word sound like a nasty tropical disease.

Judith was surprised. She hadn’t thought she was falling in love. Now, she was rather pleased at the possibility.

“Maybe I am,” she said cheerfully. “He is rather special.”

“They’ve all been special,” Marsha said.

“The schnitzel is perfect,” Judith answered, pouring herself another glass of wine.

Marsha didn’t give up easily.

“Let me know when you find out, and please, this time, don’t rush.” She reminded Judith of her first meeting with Allan and of her later disappointment. Once, Judith had fallen in love with a pilot and discovered two weeks later he was gay but confident she’d help him over it and into the elusive joys of heterosexuality, disgusting as they appeared to him. Then there had been the Chilean guerrilla who needed a home, and the doctor who dabbled in real estate and women…

“And there was James,” Judith added.

“Yes. There was James,” Marsha repeated with a sigh. “But at least he did love you. Once. In his way.”

“The only trouble with taking risks is the risks,” Judith said. “I wouldn’t want to stop taking them. And as I grow older, I want more risks—they prove that I’m still ready to learn and to feel.”

“There are other ways of proving you’re alive,” Marsha said quietly.

Perhaps it was their differences that had kept the friendship alive. Marsha tried to predict the variables, to control her emotions. She had grown up in a house of strangers, where each gesture to reach out was rebuffed. The emphasis was on form, on the outward signs. She and her two brothers had been sent to boarding schools as soon as they were old enough. In the summers they had had tutors and sports counselors, while their parents traveled on diplomatic assignments. Marsha’s brothers, ten and twelve years older than she was, had formed their own alliance. Marsha used to ache for the day she could return to school and Judith.

Only Judith knew how unhappy Marsha was. Outwardly she maintained an image of languorous wit and wealth enjoyed. She talked of great garden parties where the rich rubbed knees with the famous. She had met senators and governors, novelists whose work their Lit. class studied, J. Edgar Hoover in his declining years, and two presidents of the United States who had come to the Hilliers’ fabled parties. The one thing she had learned from her father was that a Hillier showed no weaknesses.

She had been envied for her clothes, the strange gifts and postcards her father had mailed from around the world, the gold jewelry she had received from her mother. Marsha was the first kid in their class to drive her own car, a red MGB her father sent from London for her sixteenth birthday.

On her first visit, Judith had found the Hilliers’ wealth so overwhelming she grew resentful and sullen. Later she learned to ignore it, because Marsha made it easy to ignore. That summer the Hilliers had spent a few days at home. Marsha’s father had played billiards with “the boys” and given them cigars after dinner. Her mother was a polished, hand-painted porcelain doll, fragile and silent. She composed lists for parties, visited her couturier, supervised the flower arrangements. It was difficult to imagine her giving birth to her children.

“About the only advantage of your informal education was that you learned to be alone. You don’t need others as I do,” Judith said.

“Except for you,” Marsha said, and reached over to squeeze Judith’s hand.

Over coffee and brandy they talked about Jimmy and Anne. Marsha was Anne’s godmother, a role she addressed with grave misgivings since she had no sense of religion. She had enjoyed the pomp and circumstance around Grace Church on-the-Hill, but had never learned to pray. She had sent Anne gifts, as Marsha’s godparents had sent Marsha gifts, and taken her to dinner in Toronto and once to New York when she had persuaded Judith that Anne was old enough to fly by herself.

Mellowed by the brandy, Judith passed up the opportunity of giving Jerry one more review.

***

Marsha was awake by 7:00 a.m. She decided not to go running because she didn’t want Judith to wake up alone in the apartment. Instead, she proceeded through her Tae Kwon-Do exercise and self-defense routine, including the eight basic combination karate-judo specials the instructor had bestowed on her gradu

ating class as the “if all else fails” moves of last resort. Her body felt strong and controlled. As she padded out to the kitchen to start the coffee, she was intensely aware of her calf-muscles tightening with every step, her stomach pulling into itself.

Waiting for the kettle to boil she thought of the rendezvous at F.A.O. Schwarz, struck a Sean Connery 007 pose, and greeted last night’s dishes with a supercilious smirk.

She wondered if 007 had ever washed dishes, or worried about having no toilet paper for houseguests. Would he have found some effective technique of dealing with Mrs. Gonsalves’s unique methods of retaliation? She had slopped water over the bathroom, trampled it to mud, discovered the lack of kitchen towels and left the grisly mess.

When the coffee was ready she brought in The Times and went to check if Judith was awake. Quietly she opened the guest-bedroom door.

Judith slept with her arms around the pillow, her face to the wall, knees pulled up to her chin. Her long auburn hair spread over her face. She used to sleep like that at school. Marsha remembered how much she had wished for hair like Judith’s, hair that bounced back when you put a brush through it.

She stood in the doorway. Coughed. Waited. In the end, she didn’t have the heart to wake her. Early mornings were not Judith’s best time.

Jezebel sat in her corner of the kitchen counter, sneering at her food. Marsha had switched to Kittysnacks, for the vitamins and iron the commercial promised, but clearly Jezebel hadn’t seen the commercial.

The phone rang.

“Hillier?” asked the croaky voice.

“That you, Mrs. Gonsalves?”

“Yah. Wanted to getcha before you go out. Monday my fee goes up to forty-five. Everybody charging the same now. Don’ wanna be the only schmuck on the block, know what I mean? So. Will you pay?”

“Mrs. Gonsalves, you know I’m going to London on Tuesday and I was counting on you taking care of the cat while I’m gone.”

“I know.”

“Then I guess you know I have no choice.”

“Yah. So whatcha gonna do?”

“I’ll pay.”

“One more t’ing: you don’ forget the paper towels?”

“I’ll get them tomorrow.”

Marsha slammed down the receiver and glared at the cat.

“All your fault.”

Jezebel ignored her.

Marsha took the coffee and the newspaper into the living room and flicked over the bad news on the first pages to the center. She still had two books on the best-seller list. They were the same ones as last month, but what the hell, it was late in the season, the listmakers were getting tired.

Fourteen

THEY HAD LATE LUNCH at the Sherry-Netherland, still home of the best steak tartare in New York, then walked down Fifth Avenue to F.A.O. Schwarz. Having chattered through lunch, reviewing old friends and new angles, they were now quiet.

Marsha was planning a Tae Kwon-Do strategy should they be attacked in the store. The note could have been written by a nut. She knew that Schwarz would be crowded—it always was on Saturdays. Anywhere else a crowd might be protection enough, but in New York you couldn’t count on anybody’s help but your own.

Judith was enjoying the sunshine. She loved to walk down Fifth Avenue, savoring the view of the old Plaza Hotel (she must return to the Palm Court for afternoon tea and fresh strawberries), the windows of Maison Russe, Bergdorf Goodman and the throngs of people on both sides. Two kids played hopscotch at the corner of 58th.

They turned the corner. Marsha took Judith’s arm, quickened the pace, pushing through the crowd of window-shoppers. They entered through the ornate glass doors, went past the small-item impulse-buy dolls, arranged by size and color, the seven-foot panda and its smaller brothers on the circular display stand, the games for all ages, and took the escalator to the second floor. The hands of the giant Miss Piggy clock had just moved to 3:00 p.m.

Judith, despite her determination to be alert, had that familiar sense of comfort she felt each time she came to F.A.O. Schwarz. At home with the toys. She wanted to touch and fondle them, wind them up, push their buttons, pull their strings, watch and hold them. Every hour she’d spent here had been wonderful, her visits ending in shopping sprees she couldn’t afford. In the beginning she had told herself that the toys were only for the children, so that she could appease them after an absence. But Jimmy had seen through that when he was eight and Judith had brought home the $50 electric train set.

“Look, Anne, Mommy’s bought herself a train!” he had observed. And he was right. She hadn’t known how much she had wanted that train (complete with boxcars and tunnels, lights, switches, bridge) until she had set it up in Jimmy’s room and watched it go through its loops and turns, sounding its tiny whistle.

The second floor had the trains. Judith led the way from the top of the staircase, past the Sesame Street sets, the Legos, to the far end where all the electronic toys lived. She was still seized with a sense of childlike wonder as she walked past the huge glass cases where the major-league trains ran, and around the shallow tanks with the battery-powered water toys. An attendant was demonstrating a blue spouting whale, some diving porpoises, a pink turtle and a bikini-clad doll that propelled itself forward with fast-twirling chubby arms.

Judith was bewitched by a large spotted green frog that kicked itself along, but she knew Marsha wasn’t listening. She kept scanning the crowd, turning her head sometimes to check behind her, searching for some give-away sign.

They stopped to the right of the staircase to admire the mobile corner that today included a brown stuffed monkey working out on an overhead swing.

“I wonder how they do that,” Marsha asked without a trace of interest.

“I think he must have a battery fitted into his back,” Judith said. “He’s driving the swing back and forth as he shifts his weight up and down.”

Marsha sighed.

“What do you suppose those big parrots do?” she asked, pointing up into the branches of a potted tree.

“They don’t do anything,” said an elderly woman beside Marsha. “They are purely decorative.”

“Oh,” Marsha said and started to move away.

“You hang them on a swing from the ceiling in a child’s room,” the woman persisted. “They look pretty, don’t you think?”

Judith nodded and smiled. Marsha said “aha” without enthusiasm. The Miss Piggy clock was pointing to 3:15.

“They thought you would bring your friend,” the woman said to Judith.

Marsha stopped. Judith inclined her head toward the woman.

“I beg your pardon,” she said politely.

“I said: they thought you would bring your friend along,” the woman repeated slowly, for emphasis, “and, clearly, you have.” Her voice was soft and unmodulated. “Perhaps we should walk along a bit. Look like we are old acquaintances and have just run into one another by accident. We are all shopping.” She smiled good-naturedly.

“There are some very lovely dolls this way.” She took Judith by the arm and moved forward, chatting amiably. “Your friend could follow along, since there’s only room for two people side by side.” She said to Marsha, “I hope you don’t mind.”

Marsha was too surprised to mind.

“You could try appearing a little more friendly. If someone is watching, they should think you are relaxed.” Her words came slowly, evenly spaced, as if she were taking pains with a foreign language. “As you can see, there’s nothing to be afraid of.”

After a moment’s hesitation, Marsha concurred. The woman had to be at least sixty-five. She wore an old-fashioned black sealskin coat with a fox collar, unbuttoned, and a blue-on-pink scarf pulled forward into a peak over her forehead, shading her face from the neon lights in the ceiling. It was tied into a tight knot that made a dent in her softly wrinkled second chin. Her cheeks sagged under a thick layer of too-dark rouge. A fancy pair of horn-rimmed glasses rested on a small heavily powdered nose. The tiny black eyes behi

nd the glasses were sharp, round and friendly, like teddy-bear eyes.

“We will have to be brief. We are being watched,” she said in two short bursts. They had stopped before a three-foot-high rocking horse with embroidered bridle, gilded stirrups and leather saddle. “We are interested to see that you are conducting your own investigation. That you do not fall for the obvious. That you have distinguished between what is real and what is a set-up.”

“Well, I was only… I don’t know what you’re talking about.”

“I think you do. Anyhow, we are pleased to note you are following the larger story.”

“Do you mean the George Harris story?”

“If that’s what you wish to call it—the George Harris story. We cannot know exactly how much he decided to tell you.” She glared at Judith intently through the thick glasses.

“We had talked for some time.” Judith hesitated. She thought she should pretend she knew more than she did. “In your note you said you could help me. How?”

“It depends. First, there are the preliminaries. The exchange has to have two sides. A mutuality, you might say. What, Mrs. Hayes, is your reaction to bread?”

“To what?” Judith asked.

“Bread,” the woman whispered. “We have to know. Have they already contacted you?”

“They?”

“I do wish you would stop playing games,” the woman said gloomily.

“They haven’t yet,” Judith tried.

“And you and Miss Hillier have chosen to work together. That does make the deal somewhat more attractive, though we had in mind another type of firm. Miss Hillier, I don’t want you to misunderstand, or take this as a judgment of your performance in your field, but George Harris was the perfect choice. An old, distinguished company; sole owner; being in Toronto, slightly off the beaten track. He made a terrible mistake. Lack of faith, I believe. Such a pity…” She was shaking her head sadly. She pointed at the horse. “Miss Hillier, perhaps you could go over and feel the saddle. As if you were thinking about purchasing it… That’s very good. Thank you.”

Deceptions

Deceptions Hidden Agenda

Hidden Agenda The Appraisal

The Appraisal Mortal Sins

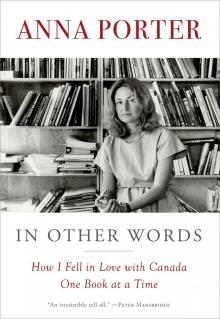

Mortal Sins In Other Words

In Other Words