- Home

- Anna Porter

Deceptions Page 3

Deceptions Read online

Page 3

“You told them . . . ?”

“That we know who she is? No. But as her picture was all over their news, it won’t take them long to figure it out. I assume you invited her to Strasbourg?”

“Who told you that?”

“Never mind who told me. Anyway, I didn’t tell their police. I couldn’t tell them and have it all over the French papers. The French don’t control their papers. It’s a stupid excuse for a country and an even stupider excuse for a government. Why would somebody want to kill this lawyer?”

Attila shrugged and raised his eyebrows to indicate he had no idea, though the first thought that sprang to his mind was that Iván Vaszary would have lots of reasons for interfering in what his wife was trying to do. Not all divorces are amicable, and the Vaszarys’ would have included more than a worn sofa, some books, and a dachshund.

“It wasn’t Vaszary,” Tóth declared.

Attila was too caught up in his worries about Helena to listen to Tóth’s theories. He had suggested her to Gizella Vaszary. He thought this would be a lucrative contract for Helena, one she might not refuse, and a chance for them to be in the same city for a while. He had tried to entice her back to Budapest, but that hadn’t worked. Strasbourg was neutral ground.

“He was in Paris. Wasn’t he?” Tóth was asking.

“Yes,” Attila said. “I was with him in Paris. He had meetings with some EU bureaucrats and a guy at the Louvre. Looked to me like he was going to spend a lot of hours in waiting rooms,” Attila said. “He told me to leave.”

“He could have hired the guy who shot the lawyer.”

“Could have,” Attila conceded.

“We can’t have one of our guys involved in a murder investigation,” Tóth continued. “Not even if we don’t like the bastard. Vaszary may still be useful for us.”

“Us?”

“Yes. Us Hungarians, in case you’ve forgotten where you sleep these days. Fucking moron . . .”

Tóth had never been smart enough to disguise who, in addition to the police department, was paying him. The last time, it had been a Ukrainian oligarch; the time before, a gang of Albanians looking to make an easy living off Váci Street shopkeepers. The whole reason for hiring Attila was now out in the open. Someone in the Gothic castle. Acting as Vaszary’s bodyguard had been too peachy an assignment from the start.

“As for the woman on the boat, I suspect it’s your friend, the art expert,” Tóth said.

“My friend?”

“Marsh, her name was, last time she darkened our lives. And you, no doubt, know why she is in Strasbourg.”

Attila affected a startled look. “Helena? In Strasbourg?”

“The coffee! Now!” Tóth yelled, and, as if she had been waiting outside for just such an order, a woman appeared bearing one cup with sugar on the side, placed it carefully on the plastic in front of Tóth (when did he decide to cover the desk in plastic?), and marched out of the room. She rolled her eyes at Attila as she left.

“You’re on the next flight to Strasbourg,” Tóth said. He picked up his cup with one pinky daintily extended and slurped. “Find out what that woman is up to.”

Since leaving the police force two years ago, Attila had managed to eke out a precarious living from a few rich clients in need of information or of evidence of something fishy in their dealings with other businesspeople, but most of his jobs were short-lived and some of his clients declined to pay his meagre daily rate. Tempting as it was, he could not afford to tell Tóth exactly what he could do with this assignment.

Besides, he needed to see Helena.

Chapter Four

The room at the Hôtel Cathédrale turned out to be a two-room suite with a magnificent view of the cathedral. It had been booked in her name and prepaid for four nights. In the hotel room’s safe, there was an envelope with a map of Strasbourg, a black circle around a house on Rue Geiler, and a short note from Gizella Vaszary, inviting her to visit at four o’clock. In the event that the time was not convenient, would she please contact Mr. Magoci, her lawyer, at his cell number to arrange another time. Mrs. Vaszary, however, urged Helena not to delay because there was considerable interest in the “object,” and some of the interested parties were growing impatient.

Helena had come with only a small holdall. Although she hadn’t anticipated a need for excessive caution, she never travelled without her thin Gerber switchblade and her Swiss mini, a handgun so tiny it could hide in the palm of her hand. These could be useful if she encountered the man who had shot the lawyer but could be a problem if she were detained by the police. She was sure every police officer in Strasbourg had her description by now. Given the number of smartphone-wielding tourists on the boat, it was likely that her photograph was also plastered all over police stations and downloaded onto cellphones. And the man might have been aiming at her, not the lawyer. She should have brought along a few of her disguises.

* * *

Helena laid the man’s beige coat on the hotel bed and patted it, looking for some sort of identification, but the pockets were empty. The coat was made of a light cotton-and-wool mix, soft to the touch. Silk lined. She thought it was the kind of material her Christie’s colleague James liked to wear. Decidedly British, somewhat androgynous, and soft-spoken, but tough, ambitious, and uncompromising, James was always correctly dressed. He had climbed the corporate ladder to some spot above middle management at the auction house. He had assumed the role of a comfortable upper-class man, though he was neither upper-class nor relaxed. Only his chewed fingernails gave him away.

James had always seemed pleased with her work and used her expertise to make himself look efficient. Yet, despite all his effort, his career had stalled, and Helena knew that he needed a big score soon.

* * *

The inside pocket had the name of its manufacturer or tailor — Vargas — in black italics sewn into the flap. A black line over the second a. That, too, was neatly sewn. Either a very exacting machine or a steady hand. In either case, expensive. As was the lining and the cologne she smelled when she patted the coat. Hugo Boss? Mont Blanc?

She called Louise and asked her to personally bring her the stylish plastic container from the office safe. Louise would know what she meant, and she would also know that something had gone wrong, or at least not as she had expected, in a routine appraisal. Could she also check for men’s wear manufacturers and bespoke tailors with the name Vargas?

The TGV from Paris took three hours if there were no delays. Even if she managed to catch the next train, Louise would not arrive until seven o’clock that evening.

It was getting to be time to visit Madame Vaszary. Helena changed into a pair of black slacks, a brown sweater, a jacket with a turned-up collar, and a brown scarf with a blue cathedral on it that she had purchased in the gift kiosk outside the hotel. She replenished her stock of tissues from the bathroom, wrapped the scarf loosely around her neck so that it covered her chin, and hid her hair in the baseball cap she used for her morning runs. Then she took the stairs to the lobby. She coughed and spluttered, blowing her nose among the nearby outdoor restaurant tables, and jogged along Rue Gutenberg, then up Rue des Francs-Bourgeois across the river from where the Batorama’s boats were at a standstill.

She blew her nose through the railway station to exit with a gaggle of newly arrived tourists. Much to the amusement of the cab driver, she gave the address of the Council of Europe, Avenue de l’Europe. “Everyone here knows that address, madame.” She apologized for her terrible cold. The driver expressed his deep regrets and gave her his card in case she needed a cab again during her stay in Strasbourg. He offered a tour of the Château du Haut-Koenigsbourg at an excellent rate once she felt better and then suggested that he could wait till her meeting was over. She declined gratefully, tipped generously, but not too generously, and walked slowly to the entrance. She walked up the steps, looked at all the flags as if she were

searching for a particular one, then turned to gaze at the field of well-cut grass.

As the cab left, she looked up at the façade, then examined the huge sign for the Palais de l’Europe, blew her nose, and sauntered slowly down to the pedestrian walkway along the river. No one followed. She joined a group of surgical mask–wearing Japanese tourists, all gazing at the massive structure. Behind them, she could see a slowly trawling police boat with four police officers scanning the entrances to the council buildings.

She crossed the river, marched along the quay, and rounded the corner onto Rue Humann where she could check her route, making sure that she was still not being followed and that no one was taking an interest in her progress. She jogged along the Avenue de l’Europe to the Boulevard Tauler and onto Rue Geiler. Number 300 was much like the other large mansions along a street, where there was nothing smaller than a three-storey French provincial, with a garden that had been fussed over and trimmed within an inch of its life. There were four security cameras pointing at different parts of the garden and the flagstone driveway. There was no police vehicle and no police officer. The only car on the street was a large SUV, comfortably far away.

She rang the bell, a commodious sound that reminded her of an orchestra’s timpani, which was followed by furious barking as something solid thumped against the door. A woman in black with a white apron and a practised smile opened the door, her left hand on the chain around the rottweiler’s neck. “Semmi baj, Lucy,” she said to the dog. “You must be Ms. Marsh,” she said to Helena. “We have been expecting you.” Lucy, who was still grumbling under her breath, clearly didn’t share the woman’s polite anticipation of Helena’s visit, but she backed up to leave room for Helena to enter. “Mrs. Vaszary is in the living room.”

All the walls were white, the furniture was white, and there were no pictures, no decoration, no books, no potted plants, no personal touches, as if the place had been staged for a prospective buyer. Some frames wrapped in brown paper sat near the windows, suggesting the tenants were new. They hadn’t had time to hang their pictures. Or, since they were divorcing, there was no point in hanging pictures.

The white curtains were open, allowing the afternoon light to fall directly onto the startlingly lifelike painting that dominated the room. At first glance, it seemed as if it were the light from the window that lit up the face of the young woman in the painting, but as Helena drew closer, she could see that the light emanated from the picture, a theatrical trick of accentuating light and dark tones to heighten dramatic tension and movement as figures emerged from the shadows. It made the young woman’s round, fleshy face shine and her half-closed eyes appear to recoil from the brightness. She wore a draped blue-and-yellow dress that revealed the rise of her breasts. In her lap, there was what looked to be a human head, swarthy, bearded, mouth set in a rictus of agony, with dishevelled hair and a bloody gash where it had been severed from its body. In contrast, the woman seemed composed, at rest, her dark brown curls cascading over her shoulders, fingers of one hand entwined in the man’s hair, the other hand holding a long-bladed sword, the blade bright red all the way to the hilt. Her fingers dripped blood.

“You like it?”

Helena turned from the painting with difficulty. A slim, platinum-blonde wearing an elegant white suit, a matching fur stole, and high-heeled black pumps stood in the doorway. “I am Gizella Vaszary,” she said. “You prefer English or French?”

“Whatever suits you,” Helena said.

Gizella continued in English. She didn’t offer to shake hands. “So glad you could make it. After all that’s happened.” She proceeded to the white leather sofa and sat, carefully aligning her legs side by side with the knees touching. She must have been aware of her skirt riding up on her thighs. “Hilda will fetch us some coffee. Unless you would prefer something stronger. . . .”

“Coffee is fine,” Helena said. “Your lawyer . . .”

“He is dead,” Gizella affirmed. “But you know that, don’t you?”

“I didn’t wait to find out,” Helena said.

“Of course not.”

“The police have been here?”

Gizella shook her head. “I was not Mr. Magoci’s only client, and it will take them a long time to interview every one of them. He was from Moldova. Specialized in corruption cases.” She shrugged and waved her hands palm up to show she had every reason to believe that most people from Moldova wallowed in corruption. “I was maybe his least important client.”

“How did you know he was killed?”

“It was on the news,” Gizella said, sweeping a bit of fluff from her skirt. “I assure you, it had absolutely nothing to do with me.”

Hilda appeared with a silver tray, two tiny white porcelain cups and saucers, a silver sugar bowl, a silver creamer, and matching dainty tongs. Gizella proceeded to pour the coffee with great care and circumspection. “Sugar?”

“No. Why, then, did he pursue the silly charade of meeting me on a tour boat, pretending we didn’t know each other? Seems like a lot of trouble to take over what should have been a simple appointment to appraise a painting.”

“I wanted to make sure you were the right person.”

“For a tour of Strasbourg? By boat?”

Gizella laughed. “Of course not. I needed the right person to give me advice about the painting. My husband and I are divorcing. We own a bit of land near Lake Balaton and an . . . öröklakás, how you say that, flat? condominium? in Budapest. He agreed that we would split all the valuables fifty-fifty. That’s fair, since we have been married almost twenty years. We have no children. The only problem is this painting. He says it’s worth maybe a couple of thousand euros, since it is a copy, and he is willing to pay me a bit more than one thousand for my share.”

“I still don’t see a reason for meeting me on a boat and pretending not to know me. We could have met in a café. I am told there are many excellent cafés in Strasbourg. Why the elaborate charade?”

“I was concerned that my husband would find out I am consulting you. We have been very cordial over the divorce, and I thought there was no need to be unpleasant. At least not yet.” She smiled at the painting and then at Helena. “It’s a very fine copy made in the nineteenth century. That’s what he told me and my lawyer.”

“Mr. Magoci.”

“Yes. He had told me the same thing before we left Budapest.”

Helena approached the painting, this time from the shady side, so she could see more of the details. The background, which had at first appeared to be solid brown, now showed faintly lit shapes that gravitated toward the central figure, hints of distorted faces, a couple with shocked, wide-open eyes. On one side, there was some mottled orange drapery with thin blue lines and dark yellow-green paint sliding downward. The hand holding the head was pale and delicate, the full, puffy sleeve of the dress pushed up to save it from the blood, the arm with the sword strong and muscular, yet there was a gold bracelet on her wrist. The woman’s face, close-up, was even younger than at first glance: pink cheeks, smooth chin pointing up, as if there were nothing more gentle and natural than to be relaxing with a dead man’s head in her lap. Its forehead was lit by the same theatrical light as the woman’s face and her barely covered breasts.

The painting was utterly arresting. Beautiful and shocking in equal measure. The bright light that focused the viewer’s eyes on the central scene suggested that the drama of this moment had already passed.

“Judith with the head of Holofernes,” Helena said. Before she moved to Florence, Artemisia had specialized in painting heroic women. Susanna, Mary Magdalene, Lucretia, and Judith. There were several versions of each, and some of them had her own features. This painting might be one of them.

“So I’ve been told,” Gizella said. “I know nothing about art,” She added.

That did not sound right, Helena thought. She obviously knew enough to question w

hat she had been told. “Your husband does?”

“He claims to.”

“When did you — or was it your husband — acquire this?”

“About a year ago. We bought it from a friend who needed money rather urgently. There was a business opportunity he could not let pass, he said.”

“Who was it?” Helena asked.

Gizella cupped her chin. “His name . . . ? Hmm . . . yes. It will come to me. We both thought it was an extraordinary painting. That’s why I had it hung in this room, even before the rest of our furniture arrived. Don’t you think it’s the perfect setting?”

“Perfect,” Helena said. “And you bought it as a copy?”

“Yes. For a few hundred euros.”

“Your lawyer said the original was supposedly in the Hermitage?”

“That’s what we were told. Except that it does not seem to be there. My lawyer made inquiries, and they do have one by her father, Orazio Gentileschi. It’s possible, Magoci said, that they have not catalogued all their canvases. Did you see her signature on the bed, below the fold of her dress?”

“Yes,” Helena said. Artemesia didn’t always sign her full name on her paintings, and she spelled it in a variety of ways. Orazio himself had written her name with two e’s in some of his letters to her. But Helena had not seen a signature with the entire surname missing. When accepted into the Accademia delle Arte del Disegno, she had spelled the whole name, with Lomi added at the end: “Artemisia d’Orazio Gentileschi Lomi.” Lomi, one of her relatives, was a good name to have in Florence, since he, too, had been a distinguished artist.

Helena ran her fingers over the paint, feeling where the artist had added layers of colour. She felt for the brush strokes, decisive, planned, certain. In her early work, Artemisia didn’t use underpainting or even sketches on the canvas. She had been one of Caravaggio’s followers — a young “Caravaggist,” adopting his startling use of light and of real, unidealized models.

Deceptions

Deceptions Hidden Agenda

Hidden Agenda The Appraisal

The Appraisal Mortal Sins

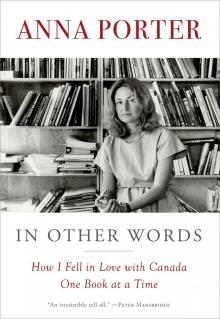

Mortal Sins In Other Words

In Other Words