- Home

- Anna Porter

The Appraisal Page 3

The Appraisal Read online

Page 3

He lay down on the sofa — not nearly as comfortable as the squishy corduroy one that had exited with the wife — and tried to read an old Jack Reacher novel, waiting for the machine to heat up. The ex had decided to leave his collection of detective fiction but took most of the quality stuff, along with the bookcases. His remaining books were still in cardboard boxes piled high next to the kitchen. He was too tired to read. Too tired to make coffee, but he persevered till 7 a.m., when Gustav insisted on his morning crap. It was barely daylight, and there was just enough rain to dissuade the dog from going outside. He hunkered down in the long passageway between the elevator and the entrance. Attila kicked the tidy cigarillo of dog turd into the darkest part of the passageway and led the disconsolate Gustav back to the apartment.

At 8 a.m., Attila was at the Police Palace (which is what everyone called the police headquarters after the government added the tall tower), showing his ID to the fat woman who had been on security long enough to know him even in the dark. As usual, she made a big production of examining his photo, looking at him, examining the photo again. Then she waved him through the X-ray machine, minus his holster and wallet. The building had become even more of a mindless fortress since he left.

Naturally, Tóth was not yet in his office, and the young uniform who guarded the second floor didn’t know enough to let Attila wait in one of the empty interrogation rooms, so he sat on the bench for petty criminals awaiting questioning. A couple of young offenders wearing American pants with crotches at their knees made room for him. They were discussing why they had been picked up and, coming up empty, focused on a girl they had both tried to take home the night before. He could have told them the reason they had been hauled in was their pants, but decided it was pointless. Most of the policemen (and sole policewoman) looked like they were at the end of a night shift, rather than starting the day. They were slow-moving, damp, bleary-eyed, and smelly.

Tóth arrived close to 9 a.m. He was eating some kind of sugary pastry that left white powder on his thin mustache — the only thin part of the man — and down his ample front. His shirt barely fit across his belly. One button had already popped, and the day had barely begun. On the other hand, his dung-coloured jacket was just-out-of-the-box new. But why, Attila wondered, had he chosen that shade of brown?

Tóth grunted when he saw Attila and motioned with his chin toward his corner office. Since Attila’s last visit, the small fringed rug and the colour photo of the smiling woman at the edge of the desk — the same desk Attila had used when this had been his office — had both disappeared. Tóth finished the pastry before he looked at his former boss and, even then, he seemed reluctant to start the conversation.

“So,” he said, at last. He sat with knees wide apart, hands clasped. “She has been on the phone all morning. We have a man with binoculars on the path up Gellért Hill and he has a perfect view of her room. She is using her own phone, not the hotel’s. We can’t get a fix on the number. She must have one of those cheap disposables you can pick up anywhere. She has a rental car, due back in Vienna in three days. The Ukrainians want her gone before then.”

Attila shook his head. “The Ukrainians? What do they have to do with her?”

“Don’t know. But they are anxious to have her out of the country. As is Mr. Krestin, the guy whose house she broke into, and he has some influence with the government. The government runs the police, in case you’ve forgotten.” He rubbed his palms together, looked at them, wiped them on his knees. “Your job is to not lose sight of her again.”

Attila sighed.

“Is that simple enough?” Tóth asked.

“Krestin?” Attila refused to be baited.

“János Krestin.”

“Guy who used to own a studio making utterly dreadful movies?”

“Him.”

“And he owned the Lipótváros football team?”

“His house is not in Lipótváros, and it’s his house that she couldn’t have been in because she was asleep in her bed.”

“If he owned Lipótváros, he has some valuables. Did you say nothing was missing?” Attila didn’t know a whole lot about János Krestin, but he did know that the man had accumulated a fortune, and some of it might have come from the bribes he collected before 1989. Rumour had it that if you were accused of petty crimes against the state, Krestin could get the state to forget about them. Or he could ensure fewer years in jail.

Most former functionaries had fitted seamlessly into the new system. Many of them had the advantages of knowing other languages, and most had done well since 1989. Back then, ordinary people were still too busy trying to repair their lives to pay much attention to the successes of others. That didn’t last.

“I said nothing was stolen except the cigar case.”

“So, what was she doing there?”

Tóth shrugged.

“Perhaps she was looking for something but didn’t find it?”

Tóth shrugged again.

“And she cut the security system. So, she is a professional?”

“Not exactly,” Tóth said, chewing on his thumbnail.

“Do you have some information about her that you are not sharing?” Attila asked. “Something that explains her connection to Krestin? You told me this Helena Marsh hasn’t been here for seven years, and, even then, no one knew what she was looking for until after she left. You remember the Bauers and their Rembrandts?”

“Vaguely. Two pictures their neighbours had appropriated during the war. She had nothing to do with that.”

“In the end, the Bauers got their Rembrandts back, and the Szilágyis decided not to prefer charges, although they told me at first that their paintings had been stolen.”

Tóth shook his head. “Irrelevant.”

“It’s not irrelevant if that’s what she does. She spent time in Germany and Holland, tracking art stolen from Jews during the war. She is some kind of expert. Is that why she is here?”

“This is not about stolen art,” Tóth said. “And Krestin was never a Nazi. He was a card-carrying party member. At least for a while.”

“A while?”

“There were no card-carrying Communists after ’90.”

Some guys, Attila thought, could easily have been both Nazi and Communist, or Nazi and then Communist. A willingness to dole out physical violence would have been an advantage after the war. A man could go a long way with those credentials. Not that Krestin had ever been accused of that publicly, but one could never be sure with men of a certain age.

“But she is, as you put it, some kind of expert on art. And if you could encourage her to leave the country, I would be very grateful,” Tóth said.

“As would the Ukrainians?”

Tóth didn’t answer.

They sat in silence for a while, Attila trying to estimate just how grateful everybody — especially the Ukrainians — would be and how much extra he could charge if he persuaded the woman to go home. Then he got to his feet, buttoned his jacket, and left. Simple enough.

He was halfway across the Szabadság Bridge when he saw her. She was wearing the same dress as yesterday but she had added a summery cotton hat and a tight-waisted white cardigan. The blue scarf was tied into a knot at her neck. She was heading to the Pest side. Striding fast, her skirt fanning out in the wind off the river, she looked like a tourism commercial: cheerful, carefree, her blond hair swept back. She glanced at him without much interest when they came face to face, but he caught the hint of a smile at the corner of her mouth. Close up, she seemed older than yesterday and older than the photo in his breast pocket. But the blond hair, the slim hips, the confident way she carried herself all added up to fortyish and foreign. Women in Hungary hadn’t walked like that for years, not since the economy tanked.

He waited for her to reach the baroque church in Ferenciek Square before he began to follow her. It was ridiculou

s to imagine she would not notice or that she wouldn’t remember swinging past him on the bridge, but he had agreed not to lose sight of her, and he was not about to let her disappear again.

She turned onto Dob Street and stopped outside a dull little café. Attila knew it; sometimes he dropped in for a cream scone. The black-clad Garda louts who had been strolling this neighbourhood for the past few months were across the street, smoking and glaring. Atilla had seen them patrolling this street and had heard that they occasionally tripped some elderly Jew on his way to the grocery shop or, better still, on his way back. Then he would be likely to drop his eggs and milk on the sidewalk. The louts would chortle and would declare that had people been more vigilant in ’44, there wouldn’t be a “Jew problem” now.

The trouble with allowing free speech, Attila thought, was that this sort of thing could go on unchecked. But then, according to the government, there was no problem. And, according to the government, the Garda had been banned. But here they were, as usual, although only half a dozen of them, unlike the past Sunday when they held a rally on Hösök Square. In the past, when Attila had arrested members of the Garda, they would be out in an hour or less. Hardly worth the effort. Tóth said the Jews and the gypsies could take care of themselves. It wasn’t entirely true, but it did save a lot of time and trouble with lawyers and foreign reporters who wanted to know why the Garda was still marching. (Local journalists knew better than to cover Garda events; the government’s media council could yank their licences.) The Garda had changed their uniforms, but they were still black, their flags were even more in-your-face patriotic, and they carried on.

Helena stayed at the café take-out window for a moment, examining the aging pastries in the glass case and checking her phone. She ordered an espresso in a Styrofoam cup, looked up and down the street (no doubt spotting him on the other side, talking to himself on his cell phone), and strolled on to number twenty-two. The lads made piggy noises but didn’t bother to cross the street.

She pressed the bell to one of the apartments. The door was opened immediately by an elderly man with thin, bent shoulders. He must have been waiting for her. It was murky inside, the only light a flash of sunshine far beyond the door. Attila took a photo with his phone but expected that it would show only the shadows.

The man let her inside and shut the door.

CHAPTER 4

Gábor Nagy was a small, fragile man dressed in a grey cardigan that sagged over his hips and grey flannel pants that seemed too big for him. His glasses dangled from a silver chain around his neck. His hand was dry and cold, but his grip was surprisingly strong. He held her hand for a moment longer than she had expected.

Géza had told her he was eighty-five years old.

“I may not be able to tell you very much,” he said in English as he led her up worn stone steps to an ornate wooden door on the first floor. There was a mezuzah to the right of the door. He touched it as he entered. Looking down to the courtyard, she saw a garden with a wild array of pink and red flowers, tall bushes in bud, and a stone pond with a green metal figure in the centre.

“We try to make it fine for those who still choose to live here,” he said, following her gaze. “This is not an easy city to live in, and houses like this are worth more demolished than not. Still,” he shrugged, “we persist.”

He ushered her into the living room, all bright and cheerful pinks and light blues, cane furniture, a plethora of cushions, as if he had been recreating a nineteenth-century spa. “I have some coffee made,” he said. “Or would you prefer a taste of Tokaji?” He spoke quickly with a soft Hungarian accent.

She shook her head. “Nothing. Thank you.”

“I have sometimes wondered what happened to him,” he said. “Although all that was so long ago that it would be natural for him to have died. Most of us did, you know. Died. And now, your call, after all these years . . .” He waved his hand. “I apologize if I was slow to remember his name. Your pronunciation made it sound American. Those names I do remember, you know. It is important to remember names. Other people I have met more recently, well, it’s hard as we get older, but those names and those faces . . . I do not usually forget.” He padded into the next room and returned with a small glass of wine. “Are you sure?” he asked, lifting the rim to his lips. “It’s very good, late harvest, picked in the ’60s. Surprisingly, I have a few bottles left. I may even have picked the grapes myself. Back then, the good stuff wasn’t exported before it had time to mature. The Russians didn’t much care for sweet wine. Now it’s Americans who buy it, and they can’t tell the difference between great and merely passable.”

She accepted the renewed offer but insisted on just enough to taste, since it was rare to be offered the real thing, she said. She knew how much it would cost now for that small bottle with five stars.

“Five puttonyos,” he told her. She sipped it to make him think she appreciated it. Her own taste was more in line with the Russians’.

“You met Géza on the train,” she prompted after he sat down in one of the cane chairs across from her. “He wants me to ask you what you remember.”

Gábor leaned in toward her and turned his head to one side, chin down. He was a bit deaf, she surmised. But as she started to repeat the question he raised his hand. “I heard you,” he said. “We met long before then.

“We were collected on the same afternoon: February 15, 1945. It was fearfully cold. My family, unlike the Mártons, had been in the ghetto, except for my uncles, who had been rounded up for labour service. Neither of them survived. We were in the cellars because of the bombardments. We had been there for weeks, sitting on concrete floors. There was no food and no heat and nowhere to bury the dead. My aunt died in early January, but her body was still there in Klauzál Square, stacked up with all the others. Frozen, of course. We couldn’t bury her. We were walled in, you know.”

Helena said she knew. She had met others who had been in the ghetto. Many had died. Gábor said they had subsisted on rotten potatoes. Some of those in the cellar applauded every time a bomb landed. They wanted the Russians to come and save them.

“We melted ice for water. My sister’s baby died. The noise was horrific, the ground shook day and night during the bombardment. The building collapsed over us. I don’t remember how we got out of there, but I do remember that we were glad to see the Russians. The joy of walking out the ghetto gate and not being stopped. The gendarmes were gone. Good to feel the air on my face. It was very cold air. No colder outside than in the cellar, but it felt clean. I could breathe. You cannot imagine the hell we had endured. Now, here they were: our liberators. That’s how it seemed to us Jews at the time. Later, we were not so enthusiastic. Géza was not enthusiastic even from the beginning.”

“You met Géza on the fifteenth?”

“Yes, I met him when we were picked up by the Russians near the Iranyi Street bakery. It had been bombed, but there was a lineup outside the ruins. They pointed machine guns at everyone and moved us along to the river where they had open trucks waiting. The only person they left behind was a woman with a baby. I showed them my yellow star (I hadn’t had the courage to tear it off yet) and my Jewish identity card from the ghetto, but they weren’t interested.”

“You said you knew Géza before the war?” Géza had not told her that.

“We were at school together, back before the Jewish laws. After that, I could no longer go to school. He recognized me, though. Did he tell you he saw me once in the summer of 1944 and pretended he didn’t know me? I was wearing that yellow star. Did he tell you?”

“He was only sixteen,” Helena said apologetically on Géza’s behalf.

“Yes. So was I.”

They were quiet for a moment.

“It was shocking to see the city. In ruins,” Gábor said. “The buildings along the Danube were on fire. So much rubble. So many dead bodies and body parts. Most places had been robbed

many times. Our Bajcsy-Zsilinszky Street apartment building had been bombed and lost its outer walls. I remember one floor was tilting downward and a piano had somehow remained stuck to the back wall. A Russian was trying to pry it loose with a gun. I don’t know how he thought he would take it home. I think the people who took over our apartment when we were forced to move into the ghetto were all killed.”

Gábor was smiling, probably at the thought of those people being killed, Helena thought.

“Old men were cutting up dead horses on the street. It was hard work. Most of the horses were frozen. The Germans left hundreds of them behind, and they had starved like us. The women and children stayed underground. You know about the women?”

She nodded. Thousands raped. Hundreds of thousands. Many killed. “The soldiers picked you up at the bakery . . .”

“They took all of us. Everyone who was lined up, except that one young woman.”

“How did they get you out of the city?”

“Trucks to Gödöllö. There were a lot of prisoners: Germans, Hungarians, soldiers, civilians. Some were children, some grandmothers. We just had the clothes we were wearing when they took us. Some soldiers still had their military greatcoats, but not for long. I wore my father’s winter jacket over a sweater and a shirt. He was in a labour camp. Géza had a loden coat. Three-quarter length, I think. They took our watches and everything else they liked, but they left me my clothes. My coat was filthy, even dirtier than their own clothes. We hadn’t washed in months.”

“They took you to . . . ?”

“Cattle cars from Gödöllö to Debrecen. No food. We were part of a shipment of loot from Budapest. Paintings, chandeliers, boxes of wine, children’s toys, a white convertible sportscar, whole cases full of sheets and towels, curtains with curtain rods, and watches, of course. They did love watches. We were in the old Debrecen Armory for some days. Maybe a week. There was some kind of trial. A military judge, a man in uniform, and a young interpreter who didn’t speak our language but seemed to be talking on our behalf. I still don’t know what the charges were. They beat Géza, but they left me alone. I thought at the time that it was because they realized I was a Jew, and they planned to send me home. But that wasn’t it. It was because Géza was a big boy and I was not. He’d been on the football team of our school. Maybe he looked like trouble. That’s when he lost his hearing in one ear, but it was dangerous not to hear well. Has it been fixed?”

Deceptions

Deceptions Hidden Agenda

Hidden Agenda The Appraisal

The Appraisal Mortal Sins

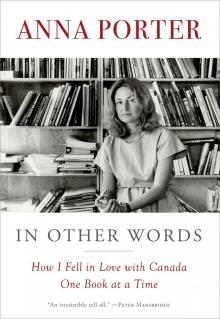

Mortal Sins In Other Words

In Other Words