- Home

- Anna Porter

Deceptions Page 18

Deceptions Read online

Page 18

Before the woman who had stood guard over her table and the Klein file folder could intervene, she took a photograph of the page.

She was about to return to the hotel, change her appearance again, and wait at the parliament buildings for Berkowitz to reappear, when she got a message from Louise: “Andrea called. She says it’s urgent — she must meet you today.”

“Where did she say she is?” Helena asked.

“She didn’t. But she said she plans to have that fabulous chestnut purée again. And she said eight o’clock. She’ll call me to confirm.”

“Chestnut purée? You’re sure she said chestnut purée?”

“That’s what it sounded like. With whipped cream. She seemed to be in a hurry. And I heard a lot of noise in the background. I thought she might have been at an airport.”

“Please book me an early flight to Strasbourg tomorrow morning. And tell Andrea that I will meet her this evening as she wishes.”

“As?”

“Myself, I think.”

“In Budapest?”

“Well, if she said the best chestnut purée . . .”

Working on the assumption that he would stay at the Gresham Four Seasons if he were in Budapest, she called the hotel and asked to speak with Mr. Azarov. The operator connected her to his room.

* * *

Since Vladimir had no problem recognizing her in her Marianne Lewis disguise, Helena again pulled on her Maria Steinbrunner fringed black wig, put on glasses, a bulky sweater, and a headband, and applied the dark red lipstick favoured by Maria. The man at the front desk gave her only a fleeting once-over, but Helena thought if she were going to continue to tangle with dangerous people, she’d better update her disguises. It would take another trip to Bratislava where Michal would construct another identity for her. These two had been perfect, down to the last detail of clothing and shoes that the deceased women would have worn, but there was no point in using an identity that no longer fooled those it had been intended to fool.

Helena locked her other passports in the safe, took the back stairs down to the lobby’s back entrance, and emerged on Kossuth Lajos Street near the kitchens. Fortunately, Maria Steinbrunner had worn her hooded raincoat, because it was raining hard and steady all the way up to Szechenyi Square. She commiserated with the two wet doormen about the weather (“It’s what we expect in October”) and marched into the massive lobby, her feet making unmistakable sloshing sounds on the marble as she advanced to the front desk. As with most front desk people at luxury hotels, the uniformed man who was just finishing with complaints about the size of a bathroom in a guest’s suite gave Helena a somewhat disapproving glance.

“It’s the rain,” Helena said in an ingratiating voice. “We hadn’t expected rain,” she added for good measure.

“Yes?” the uniform asked, as if the rain had somehow been Helena’s own fault. Perhaps none of the other guests ventured out on a nasty day.

“I must freshen up before my meeting,” she said, and marched to the women’s (‘ladies,’ in the Gresham, if you please) washroom. She removed her wig and the glasses, pulled off the check pants and replaced them with her own leggings, brushed her hair, dabbed off Maria’s dark makeup, put on a bit of light lipstick, and folded the now-superfluous clothing into her big purse. She walked out and breezed past the front desk with the confidence of a wealthy guest.

“Mr. Azarov is expecting me,” she said to the elegant waiter at the entrance to the lobby bar.

“Mr. Vladimir Azarov?” he asked, as if the hotel were full of Azarovs.

“Indeed,” Helena said.

“Did you call his room?” he asked in a tone that implied he may not want to see her even if he was in his room. But his eyes travelled to the left, past the two giant palm trees, and came to rest there for a second before returning to inspect Helena. “Perhaps you wish to leave a message?”

“Oh,” she said. “I think I will just join him in the bar.” Helena wove her way among the tables to the back of the bar where a pianist was attempting to entertain guests with a bit of Chopin. Vladimir was sitting alone behind one of the palms at a large marble-top table. He wore a burgundy velvet jacket that stretched over his broad shoulders. As the son of a Ukrainian prison guard at a Gulag labour camp, he would not have attended one of the Communist Party’s elite schools, but he still somehow managed to accumulate a significant fortune by the time he was thirty. Not long after, Putin annexed a chunk of Ukraine where Vladimir had real estate interests. Unfazed by such small misfortune, Vladimir handed over the title to his buildings to Putin’s choice of Russian oligarchs, thus establishing himself as a man to be trusted in the Kremlin.

Azarov was nursing a fat goblet of something amber that Helena assumed was brandy — his drink of choice on gloomy days, he had once told her.

He tensed when her shadow fell over his glass, but he did not look up. When she lowered herself into the leather armchair next to his, all he said was “No, madam.” He took a sip from his goblet and added in a lower voice, “Maybe another day.”

“Good evening, Vladimir,” Helena said cheerfully. “I’ve decided to accept your earlier invitation. I thought it possible, just possible, that you would be inclined to share some information.”

“Helena,” he said with a wide grin that displayed his even white teeth. But she had known him a long time and she remembered the uneven yellowish teeth he had when they first met fifteen years ago. His teeth then had been a legacy of his impoverished childhood spent somewhere near Vorkuta, where water was scarce and wells were contaminated with coal dust from the mines. It was not the kind of place where you would eat green vegetables or fruit during the long winters and, as Vladimir had told her once, his family had not been better off than the slave labourers. “Always delighted to see you,” he said. “And what information would that be?”

“I wondered whether you had managed to find the Strasbourg archer on your own? Or has your man just been following me?” she asked.

“Berkowitz? Yes. He was not so hard to find once we got his picture. I assumed he was from Hungary and, in fact, that this whole thing is some kind of Hungarian swindle that maybe we should both avoid getting mixed up in. And you do look quite lovely tonight. I don’t think I have seen this outfit and it does lend you an air of — what? — mystery, maybe.”

Helena didn’t believe he was backing away. He rarely gave up, and he would hardly have stayed in Budapest had he decided to abandon his quest for the painting. “Have you found out more than his name?”

“You mean who he works for? I think you established that when you tracked him into the parliament buildings. Still not sure how you did that, but we saw you coming out of the politicians’ and employees’ entrance.”

“That doesn’t pinpoint whom he works for, nor does it provide a name.”

“You’re right. It’s just a connection. It was your slicing up one of Grigoriev’s men that provided the answer. You were there to find out about Zoltán Nagy. Grigoriev’s man was doing the same thing.”

“Looking for Berkowitz?”

“Berkowitz works for Nagy and sometimes for Árpád Magyar. He is a kind of odd-jobs man, though he has also been an enforcer. Your buddy the police officer or private dick could have told you that. Don’t you wonder why he hasn’t?”

“No.”

“I assume he didn’t mention that Berkowitz may also be connected to Vaszary? I thought not. He lurks in a lot of government news photographs, as a kind of background, like a plant or a distant view over the Danube. He is not named in the captions.”

“Why did Berkowitz, or the men he works for, want to kill Magoci?” Helena asked.

“That,” Vladimir said, “should be your next question. Assuming you are determined to carry on with this nonsense. If I were you, Helena, I would leave it to the professionals and go back to Strasbourg where you could maybe establish

the provenance of that painting, or declare it a fake, or a copy, and go home with your well-earned reward.”

“Funny, that was also my friend’s advice — the private dick, as you call him.”

“You are not interested in taking it,” Azarov said with a grin.

“Not until I know what’s going on with that painting and why.”

Vladimir sighed. “Come, stay,” he said as he saw Helena getting ready to leave. “Let me get you a glass of wine, and I will tell you something of what I know.

“For some people, paintings are, as you know, just another form of currency. They may not be as easy to handle as other forms, but they are an effective way to launder money. You buy a painting, and no one knows what it cost you; you sell it, and, unless you seek publicity for your sale as Christie’s might to encourage other buyers or sellers, no one needs to know exactly how much you got for it. You can then reinvest your money in something clean. Like a building. Or a villa on the Mediterranean. The two gentlemen I mentioned are both richer than they have any right to be on government salaries. But once you develop a taste for owning stuff, can it ever be enough? When in doubt, my dear, I follow the money.”

“Do you know anything about Magoci?”

“A little. He was an expert in making dirty money disappear and re-emerging unencumbered by its history. In his spare time, he worked for some of the boys from my own country. They sought his advice on how to seem legitimate.”

“Including you?”

“Not me. I am my own most trusted advisor.” He chuckled. “As for you, my dear Helena, you have skills that even I envy. You could, if you wished, tell me now whether Vaszary’s painting is the real thing. You’d get paid no matter what you said. And if I had your word for it, I would gladly double your fee. Whatever it is. So long as Grigoriev doesn’t find out ahead of me. I can’t stomach that guy. I would like him to fill that giant mausoleum he calls his villa, near Sochi, with a hundred forgeries so everyone knows he is an idiot.”

Helena wondered whether the pretty Corot fake had ended up in the villa near Sochi. He had wanted something yellow for a gift for his newest wife, no doubt to distract her from her well-founded suspicions that he had found a new, even younger mistress.

“Have I told you he has about six hundred acres?” Vladimir asked. “And a life-size replica of a Spanish galleon, complete with gold bars made to look like they had been stolen from the Inca?”

“That sounds more like your old friend Viktor Yanukovych with his estate in the middle of Kiev. Didn’t you give him one of his vintage cars? Or was it the Tibetan Mastiff? There was a time you couldn’t do enough to ingratiate yourself with him and his many hangers-on.”

Vladimir smiled. “We live in a new era now, trying to wean ourselves off bribes. Have you seen Servant of the People, starring our new president, Volodymyr Zelensky? He has different ideas.”

She had barely touched her glass of Puligny-Montrachet (“Nothing but the best for the young lady,” Vladimir had said to the waiter) when one of her phones rang. It was Attila telling her what she already knew about Berkowitz, that he often worked for Magyar and Nagy on undefined contracts. He was described on official stationery as a “consultant.” He was ex-army, occasional bodyguard for visiting celebrities, a fitness geek, frequent marathoner, and, according to his police profile, a crack shot. His hobby: archery.

* * *

“Why,” Helena asked once she had walked away from Azarov’s table, “would these fine upstanding citizens of your strange little country want to have a Strasbourg lawyer killed?”

“That’s what I plan to find out,” Attila said. He put the emphasis on I. “Soon as I can stop worrying about you and . . . where are you?”

She told him that she would be flying back to Strasbourg the next day.

She had pulled on Maria Steinbrunner’s jacket and just left the Four Seasons without her wig when the phone rang again. It was Louise, confirming that Andrea would meet her at eight o’clock.

Chapter Twenty-Two

When Helena arrived at Café Gerbeaud, Andrea was already waiting. She wore a chocolate-coloured jacket, open to the ruffled neck of an off-white silk blouse that revealed her lightly tanned throat and the string of pearls that rested just an inch under the ruffles. Her cuffs extended a centimetre beyond the jacket’s sleeves. She seemed to have dressed for a special occasion.

She had taken a table at the back of the dining room, close to the lush burgundy drapes that obscured the photo gallery of the Gerbeaud’s history and the sign for the location of its toilets. Although the Gerbeaud had once been the best café and confectionery in Budapest, it had been so overrun by tourists that it no longer appealed to the locals. The last time Helena had been here, it was to meet Attila during the last day of their time together, and he had confessed that he still loved the old place. As a child, he had been overwhelmed by its grand decor, its nineteenth century charm, the chandeliers, the mahogany, the brocade, the long art deco tables where the patisseries were displayed behind curved glass, not to be touched by human hands until you plunged your finger or your fork into one of them. Attila had charmed the waitresses into giving him one of the prized tables by the windows. Although the occasion itself was sad, the last day of a romantic interlude, she remembered the café with sufficient fondness to have recommended it to Andrea as the place that serves the best chestnut purée in Europe, a fact confirmed by Andrea the last time she had visited Budapest.

A bottle of wine was already open on the table, and Andrea was eating goose liver on a thin slice of brown toast. “Exactly as I remember it,” she said. “So warm and so Habsburg. I even ordered a local wine. It’s not terrific, but it suits the place.”

Helena handed her coat to the waiter and, rather than taking the chair across from her, settled into the surprisingly comfortable chair next to Andrea. It was not only because she needed to have her back to the wall, but also because she was aware of people at other tables who had watched her progression down the long red runner carpet that led to the dining area of the Gerbeaud. A good number of them could have been Russians, and any one of them could have been connected with Grigoriev.

“Lovely to see you, too, Andrea,” Helena said. “Lovely but surprising. You never mentioned you were coming to Budapest.”

“I didn’t know that I would need to come. Tell me,” she said, leaning closer to Helena, “have you made any decisions about the painting?”

“Decisions?”

“Have you concluded if it was painted by Artemisia Gentileschi?”

“The paints, as you already know, are definitely from her period. It is not an eighteenth century copy. It is not a fake. It was not painted by another artist later than the original. But you knew that already in Rome. The tests in your lab were fairly conclusive. No matter how much you love the chestnut purée, you would not have come all this way to find out what we already knew a couple of days ago. So, tell me.”

Andrea took another sip of wine and smiled. “Well, you’re right, there is something I wanted to tell you. In person.” She waved to the waiter and ordered something from the chef’s recommendations menu.

Helena told the waiter she hadn’t decided yet. “I am here. In person,” she said to Andrea. “So, what brings you to Budapest?”

“I had an interesting discussion with the Carabinieri’s Department for the Protection of Cultural Heritage. I think you would know them as the Monuments Men. And before you ask, no, they are not all men, but they all liked that American movie with George Clooney. Who didn’t? And the name stuck. They have been exceptionally busy these past few weeks, as you may have heard, with the discovery and seizure of about a hundred thousand archaeological bits and pieces, some of which are extremely valuable. But the part that interested me was that they believe they have found some trace of a lost Caravaggio. This one is described as the widow Judith with the head of Assyrian general

Holofernes.” Andrea’s smile widened and she had a big gulp of her wine, followed by a long hard look at her friend.

“His Judith and Holofernes is in the Palazzo Barberini,” Helena said. “No one has yet authenticated the second one, the one that was found under a mattress in Toulouse. I studied the two paintings side by side at the Brera and, though I was impressed by the technique, the colours, the facial expressions — all of which seemed to be consistent with Caravaggio’s style — I remain skeptical. There was something about Holofernes’s pointy little teeth that seemed to me, at least, doubtful. Do you honestly think that yet one more attic has yielded a third Caravaggio Judith?”

“I am with Gian Pappi on the Toulouse painting,” Andrea said. “I think it’s by Finson, a talented artist and a great admirer of Caravaggio’s, but not quite in his league. And you’re right about those feral teeth. Never seen those in any other paintings by our bad boy of the Italian baroque.”

“The Louvre turned it down,” Helena said.

Andrea finished the last bit of goose liver pâté and delicately licked her forefinger. “Still, it was snapped up for $170 million by someone who didn’t need convincing. Time for you to order?”

Deceptions

Deceptions Hidden Agenda

Hidden Agenda The Appraisal

The Appraisal Mortal Sins

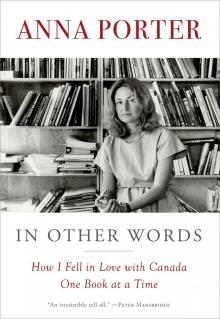

Mortal Sins In Other Words

In Other Words