- Home

- Anna Porter

Deceptions Page 14

Deceptions Read online

Page 14

“Right,” Attila interrupted. “I am about to go into Vaszary’s office, so perhaps this is a good time to tell me what the fuck is going on.”

“Your fucking phone was turned off again!”

“I was in Vaszary’s office, and he was talking. Very, very impolite to talk on my phone while our Council of Europe representative is talking. Then I was with Lieutenant Hébert, as instructed by Vaszary. Very, very impolite to talk to you while he is asking me questions about Vaszary and the murdered man.”

“Az istenfáját!” Tóth yelled.

“Exactly,” Attila said. “What do we know about Vaszary and Magoci?”

“We? Who we? I, for one, know nothing. That means there is nothing to know. If there were something to know, I would know. For sure.” The way he had put that made it quite clear to Attila that Tóth, in fact, didn’t know, that he was not happy that he hadn’t known, and that he may have been covering someone else’s ass. “I was calling you about the Russian on Rózsadomb.”

“What Russian?” Attila’s throat tightened. Rózsadomb was where the three men lived that Helena had asked him about.

“The one who was shot outside Minister Nagy’s house last night.”

“Shot? How?”

“Through one of his balls. Poor bastard. If he hadn’t called the ambulance, he wouldn’t have made it. Damn near bled to death by the time it arrived. You know anything about this?”

Attila’s immediate sympathetic reaction with that involuntary grimace most men make when they hear of someone shot in the balls vanished with his next question. “How the fuck would I know something about this when I am in Strasbourg? And why would you even ask?”

“Because the poor son of a bitch works for a Russian oligarch art collector called Grigoriev. Your girlfriend had some dealings with him last time she was in Budapest. And you were not in Strasbourg last night; you were here.”

“She is not my girlfriend, and she has no reason to be in Budapest.” Attila did know about Helena’s unpleasant encounters with Grigoriev. One of the least savoury oligarchs to have oozed out of Russia, he used enforcers to beat, kill, and threaten, and money to oil his way to his various entitlements. A year ago, Helena had run into one of his Bulgarian thugs at the Gellért hotel. “Is Grigoriev in Budapest?”

“I’ve no idea. Tell me your friend wasn’t here last night.”

“Of course not, and sadly, she is not my friend. Why would one of his thugs be at the minister’s house? Is Nagy selling his rare collection of miniature Jobbik memorabilia? Or has he stolen the triple crown?”

“You are treading on thin ice,” Tóth said portentously.

“Is the Russian still alive?”

“Barely. I want you to come back tomorrow after you deal with the police in Strasbourg. No way they can question one of our government guys. You make that clear.”

Interesting, Attila thought, that Tóth would want him back in Budapest only to help find out who shot the Russian, if whoever gave Tóth his orders thought the Russian was connected to Vaszary or the dead lawyer, or both.

Thinking about the various possible connections including Helena’s likely involvement, he walked to Les Bureaux Magoci. No police on the second floor of the building this time; only the very welcoming presence of the lovely Mademoiselle Audet, smiling when she saw Attila emerge from the staircase.

“You have decided to return,” she said in impeccable English. Her white blouse was tastefully unbuttoned at the top, her silver earrings barely grazing her shoulders. She was, maybe, twenty-five years old and much too young to give him the once-over, as she did now. “Perhaps you would like to have that appointment with one of our associates, after all?”

Attila gave her the best, most winsome smile he could conjure, given that he had been awake since 5 a.m., flown, waited, been shouted at, and sweated in his heavy jacket. “I had hoped, Mademoiselle,” he said, “that you would have time to talk with me for just a few moments.”

“Now?”

“If it’s not too much trouble, though I would prefer to invite you to lunch in the small restaurant on the river that I passed on my way here.”

“Perfect,” she said. She pressed a couple of buttons on her phone console and reached for her red blazer, carefully arranged on the back of her chair.

Although he had been trained to deal with the unexpected, Mademoiselle Audet’s response was so astonishing that he had not even had time to back away from the reception area when she rounded the corner of the desk and arrived, expectantly, at his elbow. “Oh,” Attila said. He had not expected her to accept his unintended invitation. It had been a spur-of-the-moment idea, designed to make her friendly enough to divulge some confidences.

She marched on her remarkably high heels to the elevators, pressed the down button, and turned to Attila again. “Not a busy day today,” she said. “Many of our clients are staying away since Monsieur Magoci has gone.” Attila noted that Magoci’s murder seemed to her more like a sudden departure than a death. “I looked at that restaurant several times. People seem so relaxed there. Enjoying the sunshine, you know . . .”

Attila agreed, though he hadn’t actually looked at the place and would not have been able to find it again, had Mademoiselle Audet not led the way. She walked fast for a woman teetering on seven-centimetre heels. She pulled open the door to the restaurant and went immediately to a back-corner table where there was no sunshine but a great deal of privacy. “Thought you would like this table,” she told him as she gesticulated at the waitress.

“Wine?” Attila asked feebly.

“Rouge pour moi,” she said. “And you can call me Monique. And you?”

“Attila.” He ordered a local draft beer.

“Alors, Attila,” she said, looking up eagerly. “What did you want to talk about?”

“My boss,” Attila said, “Mr. Vaszary, has been quite anxious that information Mr. Magoci wrote down at their meeting would not be made public.” A shot in the dark, but Attila suspected that not much happened “chez Magoci” that the very personable mademoiselle would not know.

“Ah, so your boss knew that my boss recorded everything.”

“You mean his notes?”

“No. I mean his recording of his client meetings. He kept voice recordings of all the meetings. He would never say he was recording, but he didn’t trust his memory on those delicate matters. Une situation delicate, ça, n’est pas? Very sensible, n’est pas? ”

Attila nodded vigorously. “Of course those would not be in his files.”

“Of course.” Monique smiled prettily.

“So, they were not turned over to the police.”

“No. They were not.”

“But you know where they are.”

“I did a lot of work for Monsieur Magoci, and he trusted me to be absolument discrète.”

Attila nodded even more vigorously but with less conviction than before. It seemed unlikely that Magoci would have taken this young woman into his confidence, but given the vagaries of human nature, it was possible. “Mr. Vaszary would be grateful if you would let him have the recording.”

“How grateful?” Monique asked, her pretty smile in place.

Attila had no idea what would be on the recording — was there more than one? — since Vaszary had not told him about his meetings with Magoci. And now he was beginning to wonder why Iván hadn’t said he knew Magoci. He thought it had been Gizella who had hired Magoci to meet with Helena on her behalf. “It depends,” he said at last. “He would have to know which meeting . . .”

“All the meetings.”

All? How many times could he have met this guy when Vaszary hadn’t been here in Strasbourg for more than a few weeks. “And Madame Vaszary?”

“No,” Monique said. “They met only once for coffee, here, in this restaurant, and I assume it was about the same

matter. You think not?”

“Really, mademoiselle, I don’t know what to think,” Attila said quite honestly.

“But you will talk with your boss and he will tell you, right?”

Extremely unlikely, Attila thought. “Tell me what?”

“What he thinks those recordings are worth to him.”

“Did you have a figure in mind?”

“A figure?”

“A sum of money.”

Monique gazed out the window and sipped her wine. “This place always reminds me of Paris,” she said. “I would like to live there in an appartement. But not too small, with a big bay window and a little patio garden, only one bedroom, I am not greedy. Maybe on Île Saint-Louis. I love those old buildings with their inner courtyards and their wide balconies overlooking the Seine. What do you think, Attila?”

“That sounds very pleasant,” Attila said.

“My mother took me to Paris when I was a little girl. We stayed at a hotel called Louis or Saint Louis or Louis the Second in Saint-Germain-des-Prés. We had to carry our own suitcases up four floors to our room at the top of the stairs, but our view was wonderful. Rooftops and garden patios with flowering trees — it must have been spring. We walked along the Seine in the evening, looking at all the boats and the book vendors and thousands of swallows wheeling about our heads. It was magic. Here, the river is too narrow and not deep enough.”

He was pondering how he could get more information from Monique without admitting that he was not here for Vaszary — at least not as far as he knew, and he was now sure he did not know enough about the Vaszarys’ dealings with Magoci. Never had known. The recording could be the key to Magoci’s murder.

“You are married?”

“What?” Attila had been planning his next attempt to find out more about Vaszary’s business with Magoci, and not thinking about his marital status.

“Are you married?” Monique asked. “I mean now, are you married now?”

“No.”

“I am also not married,” Monique confessed.

“Oh.” This may be the opening he needed, but maybe not. Still, worth trying. “A beautiful woman like you and not married.”

“Haven’t found the right man,” she said. “You?”

“I was married,” Attila said, “but it didn’t last.”

“Why?”

“I think she had other ideas for how she wanted to live.” Well that at least was truthful even if it didn’t give away much. Perhaps in this cozy atmosphere, she would think it was her turn to reveal something. “I will take your message to Mr. Vaszary, of course, but maybe you can tell me a little about the recording. For example, whether it is about a painting.”

Monique tsk ed and wagged her finger at him. “What do you think? Naturellement, it is about the painting. Please tell me tomorrow what Mr. Vaszary says. I will be here again in the morning. They have a good café au lait and pain au chocolate. Say, eight o’clock?”

Chapter Eighteen

Helena walked along the Danube, organizing her various bits of information. She wanted to decide what her next steps would be before she returned to Strasbourg and contacted Gizella Vaszary again.

The killer worked for one or more of the bureaucrats who resided on Rózsadomb. If he hadn’t gone to one of their offices when she had been chasing him, he could not have arrived back at the guard booth so fast. He must have passed the young guard often enough for them to have become friendly. They didn’t have to look up his number to call him when she told them she had something to give him.

Why there would be a lone Russian thug sitting outside Nagy’s residence was a mystery. His assertion that he worked both for Nagy and for someone else would fit the notion that Grigoriev was somehow involved. But the man who had signed up for archery classes could, as easily, have been Russian as Ukrainian.

Today’s Budapest News — the only English-language daily paper in the city — had nothing to say about the Russian, not even that he was Russian. All it reported was an accident in Rózsadomb, where the victim had been hurt but was in hospital and expected to recover. The implication was that there had been a car involved. If the man was Grigoriev’s, the Russian embassy would have made whatever arrangements necessary to keep the matter out of the newspapers. Perhaps Attila’s Russian contact would reveal more, but not to her.

She headed back to the hotel and asked the concierge for the name of a superior tailor in Budapest. She hadn’t given up on finding the shop that had made the killer’s camel overcoat.

“Someone who makes fine overcoats. I saw one that would be just perfect for my husband’s Christmas present,” she said.

“The best don’t work fast, madam,” the concierge said.

“Oh, I am not interested in speed,” Helena said. “It’s quality I want. A friend in Vienna recommended Vargas. It’s spelled vee—”

“No need, madam,” he smiled in joyful anticipation of the tip. “Mr. Vargas is two streets down, closer to the river. A walk-up. Small sign in the entrance way. Very exclusive. Coats, jackets, all made to measure, for the discerning gentleman.”

Helena thanked him with a €20 tip and asked him to keep the information secret for a few days. She wanted her purchase to remain hidden from her husband and all his friends, until she surprised him at Christmas. She looked around the empty lobby and leaned in closer to the concierge’s ear. “He has spies everywhere. It’s a game we play,” she whispered. “You wouldn’t want to spoil it now, would you?”

In her room, she changed into her black pants, her black wig with the straight fringe, rimless glasses, bulky pullover, and a headband that would serve two purposes: disguising her face and keeping the wig down. The overall appearance would not have pleased Maria Steinbrunner, a woman of expensive tastes who had spent lavishly on blond and red highlights, breast implants, and facial procedures guaranteed to keep her looking youthful. But Maria had been dead for seven years, her body deposited in a vat of acid at a Vienna building site. The police had turned up no new evidence about her killer or killers, though her boyfriend, a local organized crime boss, had remained a suspect. She was not about to complain about the wardrobe choices.

Helena had acquired her passport, driver’s licence, credit cards, and most of her personal history from the best document thief and forger in eastern Europe. He had been introduced to her as Michal — not his real name, of course — by her father, at a time when needing to disguise herself had been a ridiculous idea. She didn’t know then that recovering lost works of art would be part of her profession, or that such work would expose her to danger, and that she, too, would one day need Michal’s services.

At the time, her usual reaction to meeting her father’s acquaintances was sullen indifference. She was only fourteen and still didn’t know he was her father, but she was no longer flattered by his interest in her art studies. Annelise had explained his frequent presence with, “He is a good friend, we’ve known each other a long, long time.” When he didn’t visit for six months or longer, Annelise would become anxious, often tearful, retreating to her own room and smoking. When Helena persisted in wanting to understand why the fuss, Annelise said she worried about him. He went to some dangerous places. At the time, Helena had imagined the rather formally dressed Simon in South American jungles fraternizing with jaguars or in Africa being chased by wild elephants. When she was little, he would bring her small gifts of stuffed toy lions and hippos that did not look like their wild counterparts on television. Once he brought a doll with a blond wig, false eyelashes, and an elaborate wardrobe that Helena imagined would resemble his exotic wife, whoever she was. Simon didn’t mention a wife and when Helena asked him, he laughed. “Not everyone has a wife or a husband. Some of us are quite happy without.”

Annelise maintained that her father had vanished; she said she had never received letters. She knew he was dead only because of what

he had left them in his will. There was a live-in housekeeper, and Annelise enjoyed her travel, always first class, and usually to Europe. She would spend several weeks away from home, and when she phoned, she sounded much happier.

By the time she was ten, Helena had begun to suspect that Annelise had been with Simon during her long absences. Later, when she returned with gifts for the house — a small Picasso drawing, a Renoir watercolour, a Rubens pen-and-ink — Helena had been pleased that he had such good taste in art. By then his gifts for Helena were books about artists — the life of Michelangelo, Raphael’s life and loves — and museum catalogues with a few paintings highlighted. Having noted her lack of interest in them, he no longer brought her dolls.

Already he had begun to teach her how to identify fakes and forgeries and how easy it was to forge a credible provenance for a piece of art. “If you’re going to succeed in this business,” he had told her, “you must be smarter than they are. And the trouble is, little one, that they are very smart.”

He was talking about himself, but she didn’t know that then. Smart, mercurial, erudite, vain, cheerfully deceitful, restless, peripatetic, and amoral, her father was not unlike his hero, Odysseus, the man who believed he was invincible, that he could outwit even the gods. But, unlike Odysseus, Simon had been unable to fool everybody. And while his travels were not in the jungles, they were no less dangerous. The predators he fraternized with would, eventually, turn on him.

Two years ago, she had scattered his ashes in the Seine.

* * *

She located the squat two-storey building on Kígyó Street, a half block from fashionable Váci Street, almost hidden between two restaurants, both of them displaying English menus and pictures of gypsy violinists grinning invitingly at passers-by. There was a women’s fashion boutique, an insurance agency, and a travel bureau on the ground floor. A modest sign pointed upstairs to Vargas Benő. The name was in the same slanted script that had been sewn into the coat. It was repeated on the glass door that led into the tailor’s entranceway to a modest, well-lit room with two large tables and bolts of cloth in different colours arranged in thick layers on floor-to-ceiling shelving that surrounded the tables. A large window faced the street, and a narrow door interrupted the shelves. One of the tables was piled high with large-format pattern books. Mr. Vargas (because that, indeed, was the man’s name) emerged from an inner room. He wore a big smile, a white shirt with a cravat, and a tape measure that ran down, like suspenders, past the waist of his tidy dark trousers.

Deceptions

Deceptions Hidden Agenda

Hidden Agenda The Appraisal

The Appraisal Mortal Sins

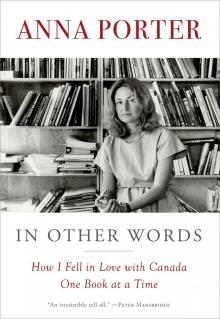

Mortal Sins In Other Words

In Other Words