- Home

- Anna Porter

Hidden Agenda Page 13

Hidden Agenda Read online

Page 13

“Will you let me know if it turns up?”

“Long as our deal stands.”

The doorbell rang. Quickly, Judith stuffed George’s note into her handbag. She turned, stopped. The bell kept ringing.

“Aren’t you going to see who it is?” Alice asked.

Judith stared at her, motionless. Her knuckles had turned white around the strap of her handbag. The high pitch of the doorbell cut through the air.

“Shit,” Alice yelled and headed for the door.

Judith grabbed her arm.

“I’ll go,” she said.

Alice shrugged her arm free.

“What’s the matter with you?” she asked, surprised. Judith approached the door, slowly. With her shoulder against the wall, she peered through the side window. She thought she recognized the limp brown hair and pink, pointed nose.

“Well,” she laughed with relief, “it’s Marlene Little. Looks like she’s got the bell stuck.”

Marlene was struggling with the bell button, pushing and pulling at it.

“I’m so sorry,” she said with a sniff when Judith opened the door.

Judith hit the button hard with the palm of her hand. The noise stopped abruptly.

“There. It always gets stuck when it’s damp.”

Marlene giggled.

“I’ve got to run now,” Alice said, side-stepping the introductions. She ran down the path, toward her car.

“Thanks,” Judith yelled after her.

“I tried to phone you, but you were out, then the line was busy,” Marlene said.

“Would you like to come in?” Judith asked.

Marlene shook her head.

“He called after you left, Scott did. I’ve been trying to get you ever since. He was asking if I’d like to go where he is an’ he said it was awful pretty there, sunny and everything year around. Not like here…”

She was studying her shoes intently, turning up her sole to get a better look.

“He said he’d take care of the plane fare and everything. He said he’d struck it awful lucky. We’d never have to worry about ’im having a job again or me having to go to work. It’d be like a long holiday, ’cept it’d go on forever.”

“Maybe you’d like a cup of coffee?” Judith suggested.

Marlene edged into the doorway but kept her eyes on her shoes.

“So, I asked ’im where he was. And he says he’s in Argentina.”

Marlene pronounced “Argentina” as if she’d been practicing for a geography exam.

“Argentina? Are you sure?”

“Wouldn’t make up a thing like that now, would I? I mean I ’ardly knew where it was. So I said to ’im, why hadn’t he called before and what in hell was he doing down there. South America it’s in. An’ he says he’d explain everything when I get there an’ I’m to pack my stuff… Not to bring much, ya know, ’cause he’d buy me everything I needed, an’ if I wanted I could have the dog I’d always been goin’ on about. And we could even get married. He’d never mentioned getting married before. Never…”

Marlene pulled a fresh bit of Kleenex out of her sleeve and blew.

“So I thought to myself, jeez, he wants me to come and get married. Then he says he can’t tell me where he is exactly, that I’m to get the ticket, one-way mind you, and he’ll phone again tonight so I could tell him when I’m coming an’ he’d pick me up at the other end. So I tell him I haven’t any money. An’ then he says I got to look in the fridge, at the back of the freezer. An’ sure enough there is this whopping wad of bills. Never seen so much cash in all my life. Look…” She pulled a big bundle wrapped in toilet paper out of her purse and shoved it at Judith.

Judith pulled Marlene into the house and shut the door behind her. She took the bundle from Marlene’s outstretched hand and unwrapped a tight roll of hundred-dollar bills.

“So, I got thinking,” Marlene went on. “It doesn’t look right all this money an’ he’s down there somewhere in Argentina and can’t give me an address or a phone number. But I didn’t tell the police when they came around asking questions. That didn’t seem right neither.”

“The police were there?”

Marlene nodded.

“I thought about it, but I didn’t. After all, Scott was pretty good to me… If he’s done something he shouldn’ ’ave, that’s his business.” She took a deep breath. “So I come here.”

“Let’s go in the kitchen and have that cup of coffee,” Judith said. “I think better on coffee.”

They sat at the kitchen table, the money between them, waiting for the kettle to boil. Marlene huddled in her raincoat, pulling it tight around her.

What did Scott Bentley do to earn that much money all of a sudden?

“Seems to me you need a few days to think,” Judith said, “maybe talk to a relative or somebody, ask their advice. I mean it would be a big move, wouldn’t it?”

“Ten hours on an airplane he said and how would I get back if I didn’t like it? An’ shots I’d have to have and a visa.” She looked miserable. “No. I don’t have any friends here and my mother, she hasn’t talked to me for a long time. She’s…well… I couldn’t call her. Anyways,” she said addressing the money, “if he’s that rich, what would he want with me? I mean later? He’d get sick of me an’ I’d be stuck down there in bloody Argentina. Don’t they speak Spanish down there? I don’t know any Spanish…”

“Not Portuguese?” Judith asked lamely.

Marlene shook her head.

“Not that it makes a difference, I don’t speak Portuguese either…” She sniffed again, then she started to snicker. “Never thought I’d need to.”

“Guess not.” Judith laughed.

“What would you do?” Marlene asked, wiping her eyes with the crumpled Kleenex.

“For one thing, I’d probably go for the visa. There’s no harm in having one even if you don’t go. And when he calls tonight, I’d try to find out how he got all that money. I’d stall for time.”

“Helluva lot of money, eh?” Marlene giggled again. “Never had more ’n a hundred bucks before. I mean at one time.”

“Have you counted it?” Judith was reluctant to touch it again.

“Six thousand.”

“Whew.” Judith lit a Rothmans. And she wasn’t going to smoke today. “Know what? If you decide to go, don’t take all that cash with you. Stick some in a bank account.” She wished she’d had as much sense when James sold the house in Leaside.

Marlene was nodding.

“I could use some to pay the rent. Would that be all right, you think?”

“I guess so,” Judith said uncertainly. She might be using incriminating evidence to pay her rent.

“I’ll phone you later,” Marlene said, stuffing the bills into her handbag and relieving Judith of her growing concern that David would arrive early and find the two of them and the money. She would feel like a rat.

Sixteen

SHE HADN’T KNOWN how nervous she was about dinner with David until now. The realization came with a bang. Searching for something suitable to wear, she tripped over a casually misplaced handbag and fell, head first, into her walk-in clothes closet. Right through the neat array of hanging dresses and into the back wall. Sprawled over the shoe rack like a beached carp.

The ruckus disrupted Jimmy’s personal rendering of “Thriller” and brought him bursting into the bedroom just in time to discover his mother with one foot caught in her handbag, trying to wriggle out of the clothes closet. Jimmy grabbed her from behind and tugged. That valiant effort brought Judith’s complete set of winter clothes tumbling down on her head. It took her five minutes to thrash out of the closet, and twenty more to put her clothes back on the hangers. A wonderful beginning to the evening.

A further side effect of admitted nervousness: she didn’t know what to wear. Not in the pleasant sense of deciding what suited best, but in the miserable sense of not looking quite right in anything. There were bulges and lumps she had not seen since

the last time she had gone into a department store to buy clothes. She looked shorter from the waist down than she had remembered. The hems of the new dresses were too long (squat calves) or too short (flabby knees), necklines too high or too low, respectively, belts curling around the front. And the left heel-pad was missing from her dark brown slingback shoes.

At 7:00 she was standing in the bathroom wearing nothing but a pair of panties and taupe tights with a run in the back of one leg. She was examining a small red rash which had crept up from her jaw over her right cheek when the doorbell rang.

“Jimmy?” she yelled.

“Yeah.” He had been sitting on the edge of her bed picking at his face. As usual, he had also been helpful, noting the occasional imperfection that had somehow escaped Judith’s attention.

“Can you open the door, please. Let him in. His name is David Parr.”

“OK.” Grudgingly.

“And Jimmy… ”

“Yeah.”

“Please come back upstairs and tell me what he’s wearing.”

By the time Jimmy slouched back, Judith had smeared half a tube of cover-all make-up over the offending rash, and over the rest of her face in case the rash decided to spread.

“He’s wearing blue jeans, a jacket and a brown turtle-neck,” Jimmy said with a sneer. Jimmy’s general response to all men Judith chose to spend time with was, at best, polite dismissal. “He looks like a cop all duded up for a date. Where are you going?”

Judith told him.

“Eating and drinking again, no wonder you have to go on diets all the time.”

Judith pulled on a pair of tailored jeans, a loose-fitting pink angora sweater, and topped it off with her suede jacket. She brushed her hair rapidly, swung the offending handbag over her shoulder, took a deep breath, then practiced smiling all the way downstairs.

“Hello, David.” With a light touch.

He was standing by Anne’s record collection, tilting his head to read the titles on the spines.

“Lovely as ever,” he said. His eyes scanned her body as if he were trying to commit her to memory.

Judith was glad she hadn’t put much lighting in the living room and attempted to lounge casually in her angora sweater (should I have worn a bra?). She fixed him a tall Scotch and water. Soda for herself, no overindulgence tonight. Then she put on Anne’s favorite Rolling Stones, progressive but not lurid, and examined David from the safe confines of the coffee-stained blue armchair by the fireplace. He had the casual grace of a frequent visitor. The shabby room had grown soft and cozy around him.

“You don’t look half bad yourself,” she said warmly.

“Now, that’s a surprise!” David said. “I’ve come right from the scene of a compact little assault and battery. A schoolteacher found his wife in bed with the cabdriver who’d delivered her home from the supermarket. So he bumped the cabbie over the head with the standing lamp—old-fashioned wrought iron, the only decent piece of furniture in the apartment—then punctured him with the kitchen knife. Awful mess. Then he got his wife in the back as she was running out to get help. A small guy, too. You wouldn’t have thought he had so much strength. Poor bastard was curled up on the floor whining by the time we got there.”

“What’s going to happen to him?”

“He’ll get five to six if he’s lucky. Cabdriver may survive. Wife should be all right. The knife didn’t go in very far. I shaved in the car on the way here and picked up the turtleneck from Levine’s. I figured it was better to arrive on time than to try to dazzle you with my appearance.”

“You must be tired,” she said, searching for conversation.

David shook his head.

“I’m used to it. What about you? How can you seem so all-together after the kind of day you’ve had?”

“What do you mean?”

“Tracking down those witnesses. Such tenacity, such endurance…”

“You had me trailed?” she yelled, indignant.

“Relax. Coincidence—we were following the same routes, that’s all. We’re still searching for the manuscript. And not finding anything. Did you?”

It flashed through her mind that he knew more than he let on, but she didn’t like the idea. He had settled into the sofa, one arm draped over the back, the other cradling his glass. Comfortable, reassuring. Any thought of duplicity jarred with the pose.

“Did you?” David repeated the question. He hadn’t noticed her hesitation.

“Not much,” she said. Then again, he might have had her followed for her own protection. What was it the woman had said: continued well-being?

“Have you found the guy with the briefcase?”

“Muller? No.”

“That’s Muller. Then there was the cabdriver you mentioned, Scott Bentley, and Mrs. Hall. Don’t you think it’s strange that four out of six have vanished?”

“I do.” Parr took a big gulp of his Scotch, then coughed, apparently unused to gulping Scotch. “What do you make of Marlene Little?”

“She was looking the other way,” Judith said quickly.

“You believe her?”

“Yes. And I’ve done of lot of interviewing—I can usually tell when people are lying.” No. She was not going to give this one away. She’d tell him everything else she knew, but not this. She wouldn’t betray Marlene’s trust.

David nodded.

“I believed her too.”

“What about the black woman with the big shopping bag?”

“Yes. We found her,” David said. He walked over to the kitchen counter and poured himself a refill. He swirled the Scotch around in his glass as he came back into the living room, but stopped in the doorway.

“She’s dead,” he said quietly.

“No! I don’t believe it! How?”

“Suicide. She was from Jamaica. An illegal. Cleaning in Forest Hill and Rosedale. Cheap labor for your waxed hardwood floors. Each year there are more of them. You see them between 7:00 and 8:00 in the morning, heading up the rich streets in waves. But they have their dues to pay. Protection money to buy guaranteed silence, anonymous contacts who find them jobs where there are no tax forms to fill out. Sometimes they get squeezed so hard there’s nothing left for the family they support back home. Those who dare, leave and start again in some other city. The weak ones often collapse.”

“How did it happen?”

“She took an overdose of sleeping pills. Or so it seems.”

Judith looked at him quizzically. He hunched forward, his elbows leaning on his knees, his head down. A strand of sandy-brown hair dangled over his face.

“Do you believe that?”

“No.” His voice was barely audible. “But I have nothing to go on yet. Not with her. Nor with the others. Take Scott Bentley, for example, a drifter, a doer of odd jobs. No reason why he shouldn’t drift on. He’s been moving around all his life. And Jenkins—he was a relief driver for another cabbie. Lived in a rooming house. Before that, he was in other rooming houses in Toronto, and elsewhere. We’ve checked him through the computer. He’s been in and out of jail since he started to walk. Petty larceny. Theft. An assist in a burglary. A stint of free-lance enforcing. Check fraud. Nothing major, though you wouldn’t want to run into him in an alley.”

“Was Jenkins his real name?”

“He’s had others. We traced him through a composite drawing.”

“He wasn’t carrying anything big enough to hide a manuscript. What about Muller? Have you traced him?”

“He gave us a false ID. A lot of people do when they’re witnesses to an accident. Ordinary people we wouldn’t have on file. They just don’t want to get involved. He appeared to be a businessman. Three-piece suit. Chain-smoker. Maybe he was from out of town and worried he might have to stay for an inquest. Maybe he didn’t want his name in the papers. And Mrs. Hall. Why shouldn’t she take a holiday? It’s nice to have a winter vacation and she could certainly afford one.”

“Does her son know where she went?”

/> “No. He says his mother takes holidays alone and why should she consult him about her plans.”

“Close family.”

“But not unusual.”

“No.”

“That’s just the point. None of the stories is unusual in itself. When you put them together… I was thinking about the two guys who caused the disturbance upstairs. Happened to be at the same time as the train was pulling into the station. It was over as soon as Harris was hit. Another coincidence?” He paced around the couch, then sat down again. “Is this what you wanted to talk to me about?”

“Yes. And no—mainly I wanted to tell you what happened in New York, and to show you this.” She handed him the piece of paper Alice had given her.

Jimmy pounded down the stairs, wheeled around the bannister and swaggered into the kitchen.

“Time for my supper,” he growled. “Which can should I be opening tonight?”

“The macaroni special—your favorite,” Judith said. Why couldn’t he be a touch more civil?

He came back and leaned against the doorframe.

“I’m having my ear pierced,” he announced.

“You what?”

“Ear, you know, ear,” he was pulling at his right earlobe, “pierced.”

“Not tonight, OK? I’m really busy tonight. OK?”

“You’re always busy,” he said and turned his back. “Sorry. Thought you might like to know.”

So it was going to be hardball. Must have learned how to play from Granny. Judith followed him into the kitchen.

“Jimmy,” her voice was rising, “please. You can see I’m working. It’s important. Could we talk about this stupid ear thing tomorrow?”

“Sure. Hope you’ll like my earring.” He was opening the Mamma’s macaroni, slamming the can onto the counter each time he turned it.

Deep breathing. She would not allow herself to be goaded into losing her temper—not with David in the living room.

“You are not,” she said evenly, “going to have your ear pierced tonight and if you keep this up—you’ll never have your ear pierced.”

“It won’t be so long before I’m eighteen,” he said, his voice cracking.

Deceptions

Deceptions Hidden Agenda

Hidden Agenda The Appraisal

The Appraisal Mortal Sins

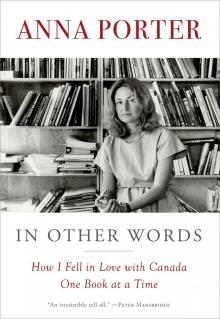

Mortal Sins In Other Words

In Other Words